Variations on Modernism, 1930-1970

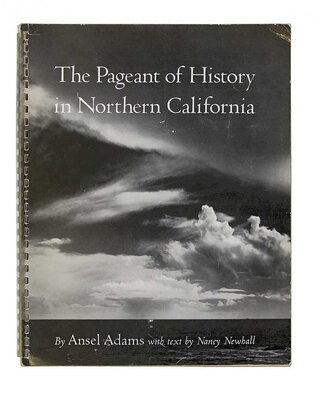

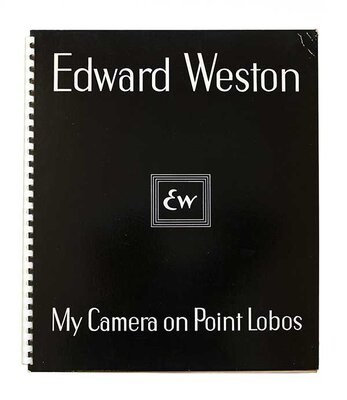

Photographers in America and Europe found a variety of ways to build on Stieglitz’s zeal to reveal the aesthetic and expressive possibilities of photography. In America, Ansel Adams and Edward Weston spearheaded the f64 group in California. They called on photography to present the world (especially the natural world and the human body) ‘as it is’ through exceptional clarity, careful composition, minimal cropping, and a final print that brought out the full tonal spectrum, from the whitest whites to the deepest blacks. Pure objectivity could reveal the greatest truths. In the years following WWII, artists lost their faith in objective truths. They still pointed their cameras outward, toward the same subject matter, but did so in service to an inner vision. The rigorous objectivity of Adams and Weston gave way to the more novelistic musings of Wright Morris, and the mysticism of Minor White. The purity of form was still celebrated, especially in the Japanese Eikoh Hosoe’s images of nudes, but through a highly personal and expressionistic visual language.

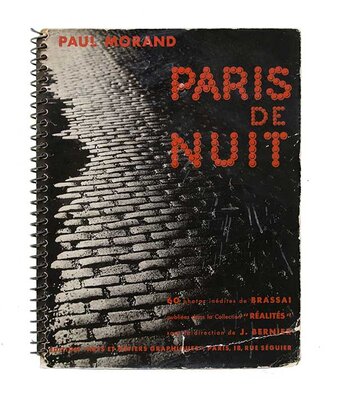

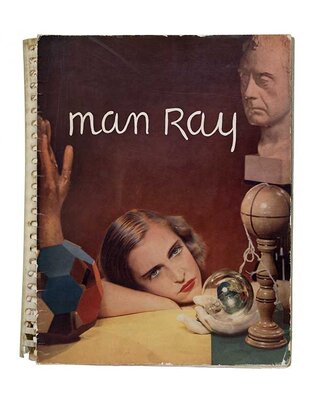

European photographers (and a few Americans) were more experimental. Objective reality gave way to the primacy of the subconscious or, alternately, a hyper-objective reality only visible through photography. Influenced by the functional formalism of the Bauhaus in Germany and Surrealism in France, these artists were interested in what photography could capture that the eye could not. The unusual angles, radical croppings, extreme close-ups, double exposures, and solarizations of Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Berenice Abbott, and others expressed new visions for a changing society. Sometimes the subject matter itself was new or seen in unconventional ways, as in Brassai’s nighttime photographs of Paris that revealed familiar views to be hauntingly strange and mysterious.

Other photographers turned toward a more “humanistic photography” in their images of everyday life that are at once journalistic in their specificity and formalist in their recognition of the visual lyricism of the commonplace. Most were influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s famous “decisive moment”—the moment when the camera becomes an extension of the eye and the subject matter and the formal pictorial elements coalesce in the viewfinder to make the perfect photograph. Paul Strand, who had helped usher in Modernism in the last issues of Camera Work, broke away from the sterility of pure form in favor of documentary studies in Europe and America that emphasized the dignity of quotidian humanity. His European counterparts, including André Kertész and Robert Doisneau, trained their cameras on Paris, essentially recording the city “before the war” and “after the war,” respectively. The lighthearted yet formally sophisticated charm of their photographs stood in stark contrast to the darkly poetic images in Pierre Jahan and Jean Cocteau’s La Mort et les Statues (1946). Jahan’s images of the Nazi-destroyed sculptures were emblematic of the war’s destructive impact on civilization and humanity itself.