US colonialism as examined by Filipinx and Asian American scholars

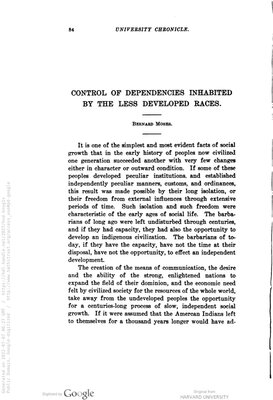

The Bancroft Library’s collections include the personal papers of David Prescott Barrows and Bernard Moses, which document their early involvement with American colonialism in the Philippines, especially their work in redesigning the education system. Filipinx and Asian American studies scholars have used these collections to critique colonialism and its aftermath and to expose the belief in white supremacy underlying what scholar Renato Constantino calls the “mask of benevolence.”

The people of the Philippines fought for their independence from Spain and declared the First Philippine Republic in 1899. Instead of acknowledging the republic, the United States colonized the Philippines by force. The ensuing Philippine-American War—generally periodized between 1899 and 1902—caused at least 200,000 civilian deaths amid famine, disease, and war crimes committed by American troops. Historians of the war, however, extend its timeline to 1913, when the United States’ military invaded, decimated, and colonized the Sultanate of Sulu—an independent Muslim state—into the Philippines, which raised the death toll significantly.

In 1900, President William McKinley appointed Bernard Moses (1846-1931)—a professor of history and political science at UC Berkeley—to the Second Philippine Commission, known as the Taft Commission, to make recommendations about governing the Philippines. Moses was chosen because of his expertise on the subject of Latin American colonialism. That same year, future American President William H. Taft, president of the Taft Commission, appointed David Prescott Barrows (1873-1954) as superintendent of schools for Manila. Later, Barrows became chief of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes for the Philippine Islands, and in 1903 was appointed to the position of general superintendent of education for the islands. In this capacity, Barrows completely reorganized the Philippine educational system. His textbook, A History of the Philippines (1903), was highly influential and remained the official high school history textbook in the Philippines until 1926. In 1910, Barrows was appointed professor of education at UC Berkeley and became president of the university from 1919 to 1923.

In 1963, the university named Moses Hall in honor of Bernard Moses. The proposal to unname the building was approved in February 2023. The authors of the proposal note that “Moses’ white supremacist views are not incidental to his work. Rather they are central to his views about history, society and politics. They are reflected in his academic writings about colonized people, both in the Americas and elsewhere in the world, and in his discussion of Black ex-slaves and their descendants in the U.S. They are also central to a ‘problem’ that he discusses in several works: the problem of how white people ought to relate to non-white people, and of how to make sure that their interaction does not impede the progression of Western civilization.”

The university named Barrows Hall in David Barrows’ honor in 1964; the name was removed in 2020 after years of protests by activists. The Building Name Review Committee in its recommendation letter to Chancellor Carol Christ noted that “[i]n his scholarship, Barrows expressed and extended the white supremacist assumptions that he applied as schools chief in the Philippines [… which] reflect racial ideologies consistent with the ‘humanitarian imperialism’ of his time.” The committee also reported Barrows' disdain for the Filipinos’ right to self-rule, and, in terms of his education policy, referenced his belief that “Filipinos were an ‘illiterate and ignorant class’ [that needed] to be brought into modernity through the benevolence of American rules.” Furthermore, according to the committee, “Barrows underscored that Europeans and white people were the only ‘great historical race,’ against which all others are to be compared.”

‘Education as an instrument of colonial policy’

“The molding of men’s minds is the best means of conquest. Education, therefore, serves as a weapon in wars of colonial conquest. ...

“The primary reason for the rapid introduction on a large scale, of the American public school system in the Philippines was the conviction of the military leaders that no measure could so quickly promote the pacification of the islands as education. ...

“The first and perhaps the master stroke in the plan to use education as an instrument of colonial policy was the decision to use English as a medium of instruction. English became the wedge that separated the Filipinos from their past and later was to separate educated Filipinos from the masses of their countrymen. ...

“With American textbooks, Filipinos started learning not only a new language but also a new way of life, alien to their traditions and yet a caricature of their model. ...

“The emphasis in our study of history has been on the great gifts that our conquerors have bestowed upon us. A mask of benevolence was used to hide the cruelties and deceits of early American occupation.”

—Constantino, The Miseducation of the Filipino, pp. 3, 7-8, 16

The role of an American textbook in shaping Filipino consciousness

“David Barrows ... published A History of the Philippines in 1905. Testimony to its importance [,] was its reappearance in a new edition as late as 1924. ...“It is fair to say that the official textbooks for public school use were much more influential than their rivals in shaping Filipino consciousness through this crucial period of nation-state formation....“And when one considers that the text was read by Filipino public high school students—the future professionals and politicians of the country—for at least two decades, its impact cannot be overstated. ...“Filipinos were being educated to think of themselves as belonging to a race that has its own place—not just a habitat, or an ‘island home,’ but a place in a racial hierarchy. Students were to locate the position of the Filipino race in an evolutionary ladder that featured the most advanced (or European) at the top to the most primitive (as found in areas like ‘the Far East’) at the bottom."

—Ileto, Knowing America’s Colony, pp. 3-4.

‘Educational research requires an analysis of colonialism’

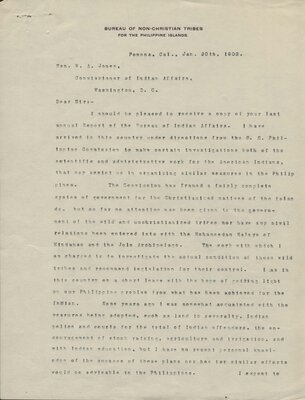

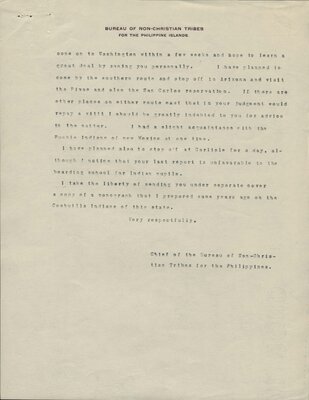

“In 1902, David P. Barrows, Chief of the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes, sailed from the Philippines back to the United States on a fact-finding mission. Upon his arrival in California, he contacted the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, W. A. Jones, in Washington, DC:

‘Dear Sir:I should be pleased to receive a copy of your last annual Report of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I have arrived in this country under directions from the U.S. Philippine Commission to make certain investigations both of the scientific and admisistrative [sic] work for the American Indians, that may assist us in organizing similar measures in the Philippines.’ ...

“[Barrows’] research on U.S. Indian education policy would serve him well when the Philippine Commission appointed him General Superintendent of Education in 1903. As was the case for the American officials before and after him, Barrows’ comparison of U.S. colonial and racial schooling models shaped the development of American education policy in the Philippines. ... For this reason, educational research requires an analysis of colonialism.”

—Hsu, “Colonial Lessons,” pp. 39-40.

‘The white man’ and ‘less developed races’

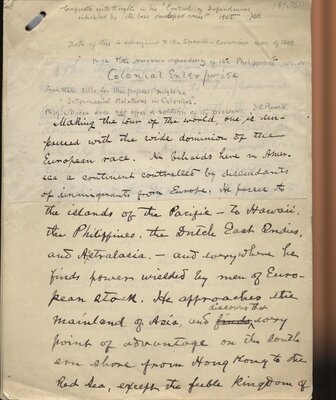

“Indeed, when designing the system of education in the Philippines, colonial officials looked to models of schooling that were geared toward the other ‘problem’ races instead of examining the educational systems popularly used in the recently incorporated U.S. states, revealing that the intended goal of education in the Philippines was not to train Filipinos for participation in democracy but rather to produce them as racialized ‘others.’...“When Bernard Moses was appointed to the U.S. Philippine Commission to tackle this problem, he brought with him the legitimacy of an academic and the ideology of white racial domination. A March 10, 1900, newspaper report identified Moses as a ‘professor of history and political economy in the University of California.’ … The article further explained that ‘The special subject of Prof. Moses’ historical researches [sic] has been the colonization and development of North and South America.’...“In a speech entitled ‘Colonial Enterprise,’ Moses shared the following conclusions on the study of colonialism: ‘In all these undertakings, [the] student discovers his chief interests not in the events of the conquest, not in the formation and establishment of a government, not in the efforts to eliminate the unruly and to preserve order, but in questions concerning the relations the white man holds and is to hold in the future to the numbers of the less developed races.’”

—Hsu, “Colonial Lessons,” p. 49

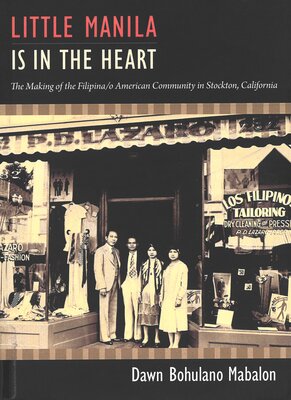

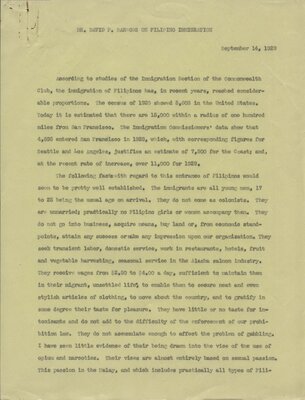

‘The defects of the race’

“In 1929 the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco brought together experts in law, medicine, and science to debate Filipina/o immigration. The most incendiary testimony came from David Barrows of the University of California, formerly superintendent of schools in Manila and director of education in the Philippines, who confirmed anxieties about Filipina/o racial difference and Filipina/o hypersexuality.“‘Their vices are almost entirely based on sexual passion. ... The defects of the race are not intellectual but moral, and it is on the moral side that Filipinos require inflexible standards and constant support.’”

—Mabalon, Little Manila Is In the Heart, p. 143

A ‘wise and beneficient’ authority over a ‘rude people’

“Moses reviewed the history of British colonialism in Asia and Africa and found that it had been ‘reckless and tyrannical.’ Because of England’s monarchical tradition, it had failed to live up to the promise of developing the ‘lesser races.’ In contrast, the United States was special. Because of its unique democratic history, Americans were endowed with a liberal character unmatched by any other. Thus, only the United States would be able to construct a ‘wise and beneficient [sic] governmental authority over a rude people.’...“Of course, proponents of liberal exceptionalism could not point to the Philippine-American War as evidence for America’s special liberal imperialism. The brutality of the war betrayed the self-proclaimed image.”

—Go, Patterns of Empire, pp. 69-70.

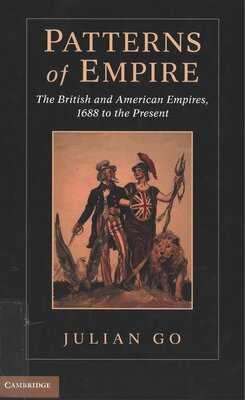

Moses published his opinions about the “less developed races” in the University Chronicle, which he founded in 1898, as the University of California’s first professor of history. It was subtitled “An official record” and was “intended to furnish a record of such events in the life of the University as may be of general interest.” Moses’ theories of white supremacy were deemed by him worthy to be published in the official record of campus intellectual life.

—Moses, “Control of Dependencies,” p. 69.