Propaganda

“THE CRITICAL ISSUE FACING the Bolsheviks in 1917 was not merely the seizure of power but the seizure of meaning.”

--Victoria E. Bonnell in “Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin.”

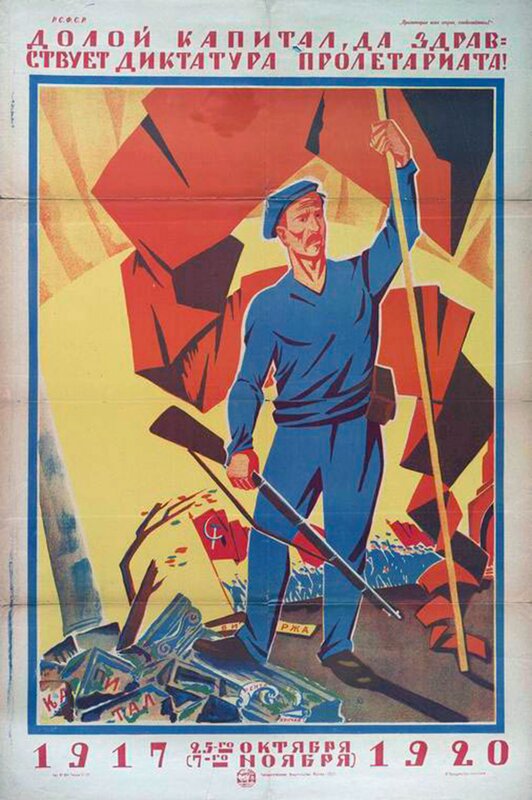

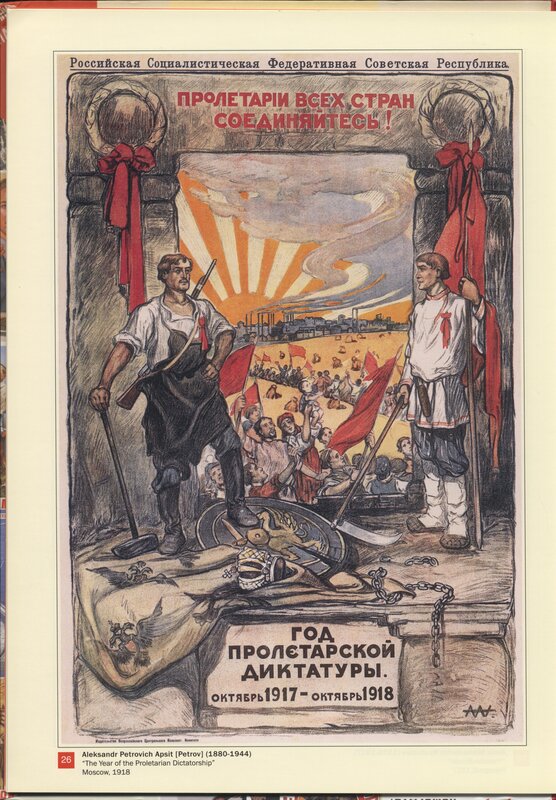

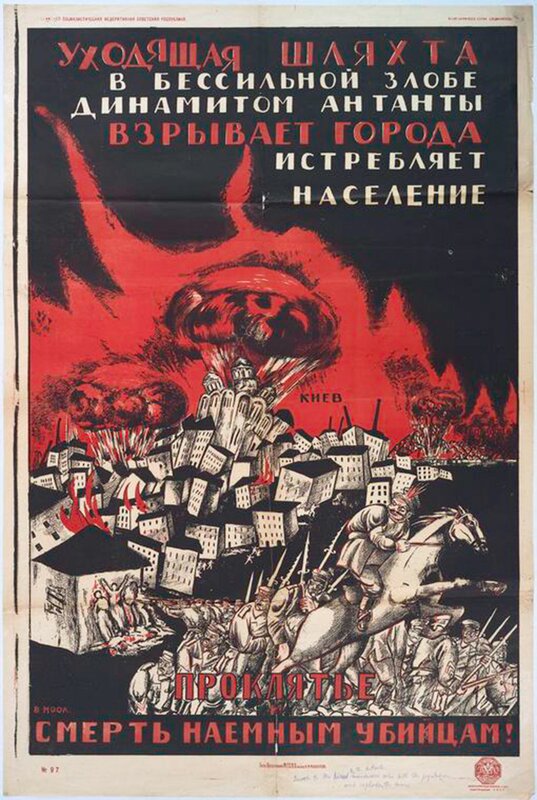

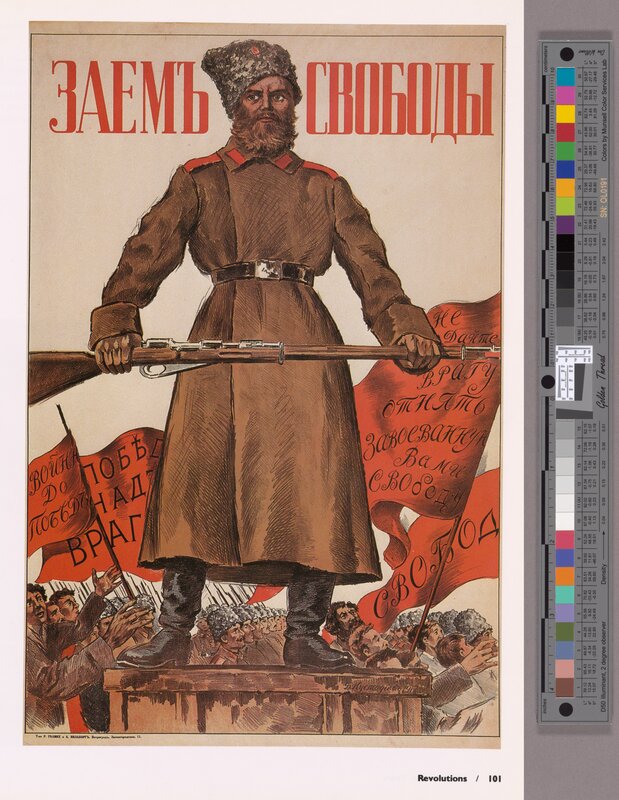

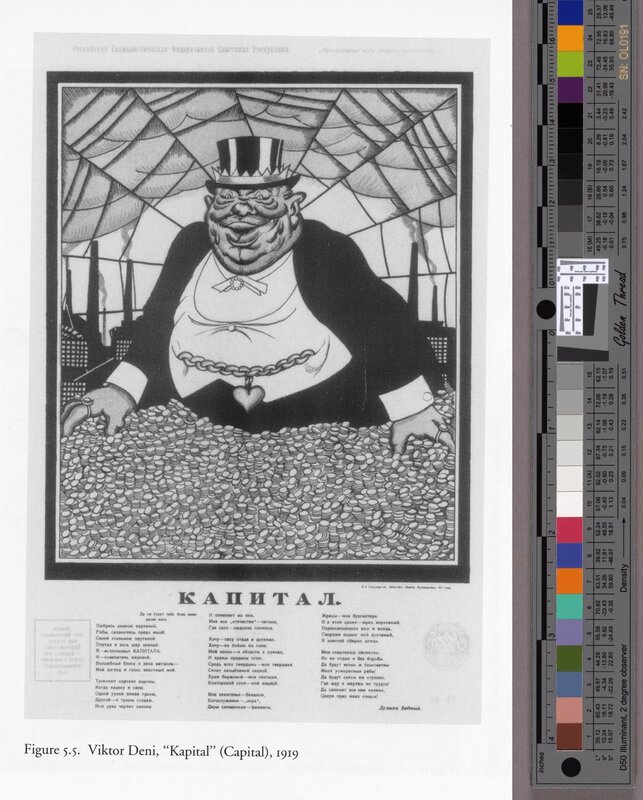

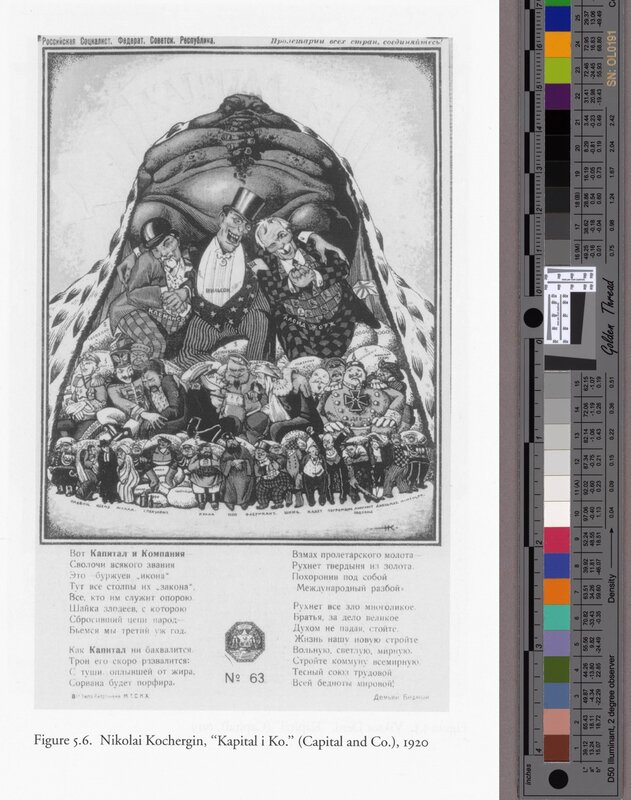

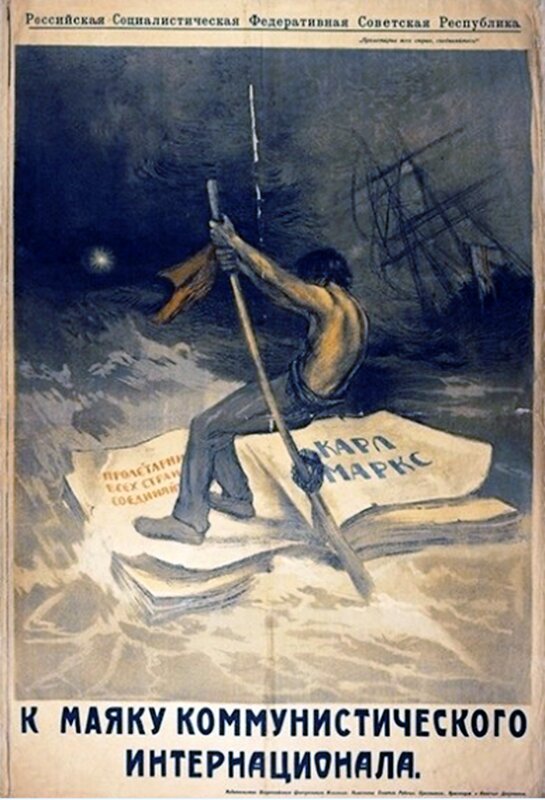

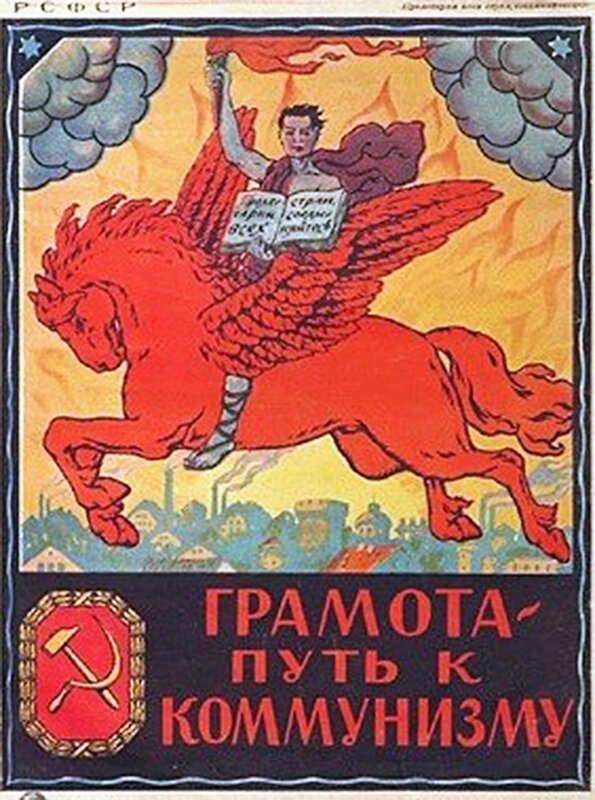

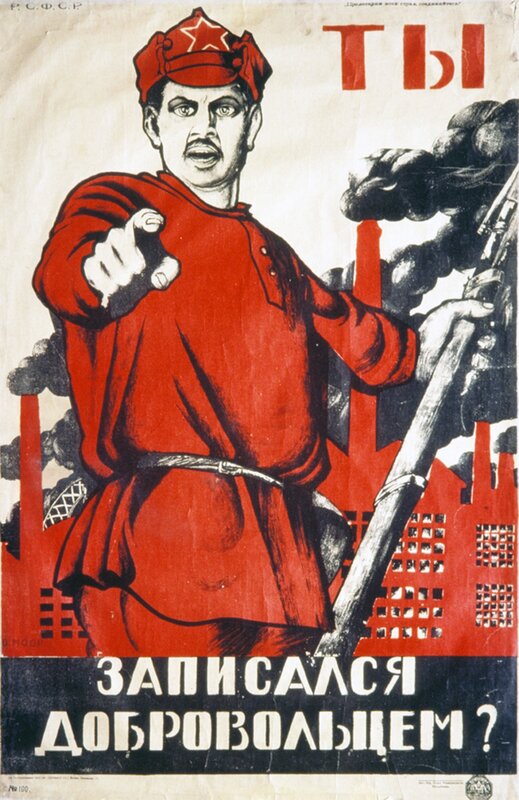

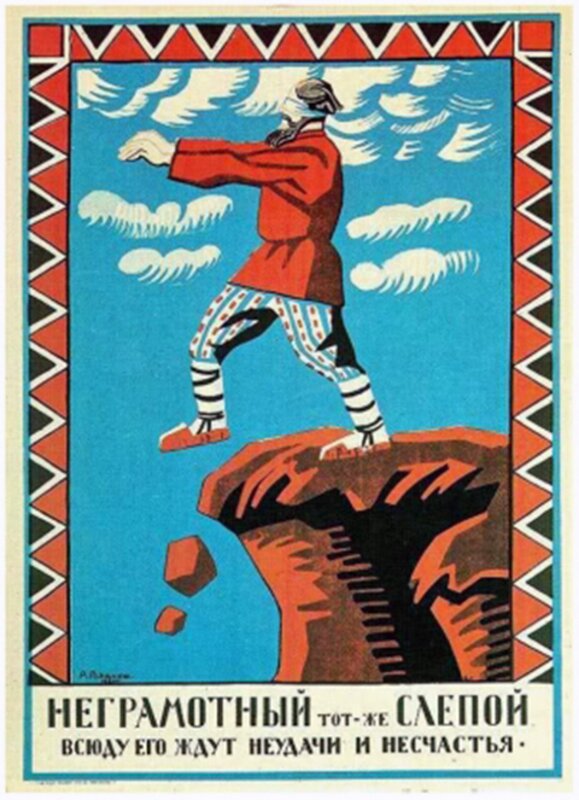

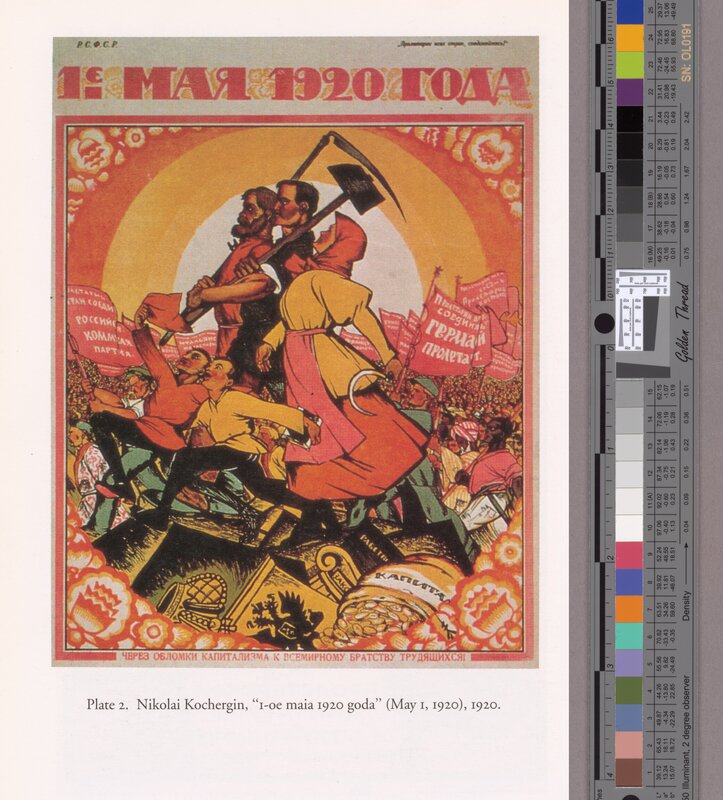

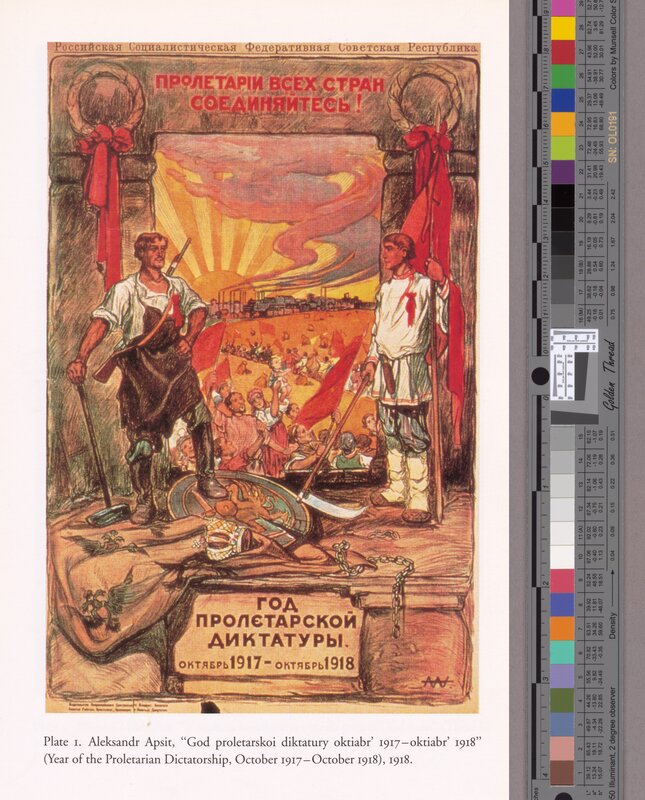

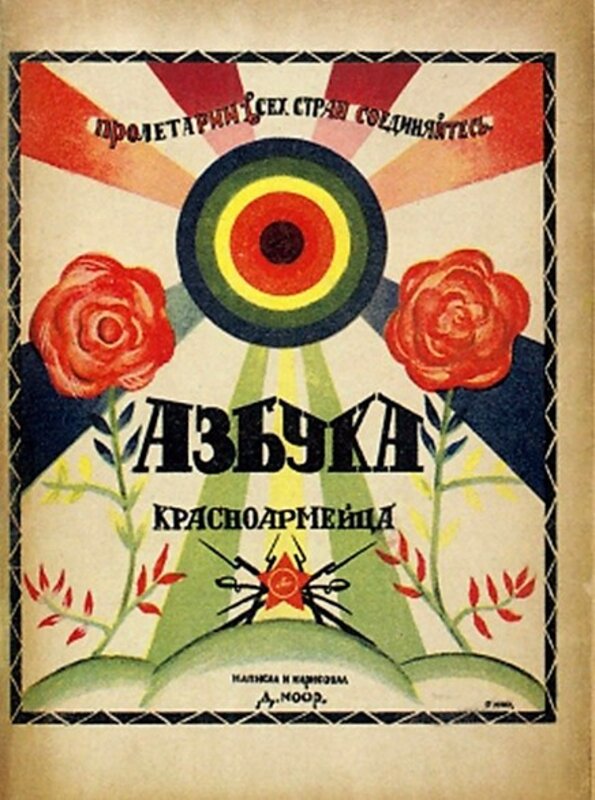

The Bolshevik revolution that was followed by the counter-revolution and the civil war had to resort to use multi-modal propaganda that was directed towards winning the hearts and minds of the people it tried to rule. In her seminal work, “Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters under Lenin and Stalin,” Professor Victoria E. Bonnell of UC Berkeley states that these political propaganda posters displayed carefully chosen images, and crafted messages that were aimed at creation of “Homo sovieticus.” These posters are indeed the objects that portray the notion of power. As Professor Bonnell states that the problem of interpretation these visual narratives also is associated with the context in which these were created, functioned. Thus the multitude of lenses of interpretations of contemporary analysts must take in consideration also the “eyes of the Russian and other populations” that constituted the multicultural, multilayered and multi-ethnic Russian Empire in the immediate aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917. Given the relatively low literacy rates in the Russian Empire, gauging the impact of the words as these are displayed on these posters becomes problematic. However less problematic are the images themselves. Through the colorful images that cued the silent non-verbal messages that were intended to persuade the population at large, the revolution tried to regulate the notions of authenticity. The binaries of Capitalist oppression against the Peasants and Workers or that of the White Russians against the Red Guards became cultural signifiers that sub-consciously tried to force their way in the psyche of the masses. When the Empire had collapsed, the vestiges of the old structures of Imperial power and glory had to be replaced with the new. These posters as cultural objects then became the primary texts that had to be interpreted, reinterpreted and internalized under the watchful eyes of the emerging new structure that envisioned the leadership of the party. While this interpretation glosses over the complexities of revolution, counter-revolution, the civil war that ensue, it does however provide a semblance of meaningful framework for analyzing these posters today.