Etel Adnan: Painting in Arabic

Right: Detail from Etel Adnan, Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Rihla ilâ Jabal Tamalpais), 2008, leporello (watercolor and Indian ink on Japanese paper), 54 pages. Collection of Museé de l’Institut du monde arabe, Paris.

Born in Beirut, Lebanon, artist and poet Etel Adnan grew up in a fraught political environment that shaped her unique connection to language. Following the end of World War I, Allied forces occupying Lebanon placed it under French military administration, and the implementation of French convent schools led to the forced adoption of the colonial language across the country. Adnan witnessed punishment and stigmatization as a result of speaking Arabic throughout her schooling.

Adnan’s family mainly spoke Turkish and some Greek in her early life, but the widespread use of French eventually made its way into the household. Worried about this estrangement from Arabic, Adnan’s father tried to teach her the language by instructing her to repeatedly copy the alphabet by hand. Adnan found pleasure in copying letters and words she did not understand, a graphic process that laid the foundation for her future art practice.

In the 1950s, Adnan studied philosophy in Paris before continuing her education at the University of California, Berkeley, eventually becoming a philosophy professor in the Bay Area. This period of her life coincided with the onset of the Algerian War of Independence, and Adnan grew deeply conflicted with her relationship to the French language, resenting that it was her main language of self-expression as a poet and writer.

Though Adnan taught classes on the philosophy of art, she did not practice art on her own. When a colleague suggested she try painting, Adnan followed the advice. She took to it immediately, and saw painting as a new language, explaining that “Abstract art was the equivalent of poetic expression. I didn’t need to use words, but colors and lines.” Adnan found that this practice of “painting in Arabic” resolved some of her conflicts about writing in French as it allowed her an open form of expression. She also began to incorporate color and calligraphy into compositions on paper, which mainly took the form of accordion-fold books or “leporellos.” This marked a direct return to Arabic script, and the faithful repetitions of Arabic words and verses in her work echo the copying exercises from her childhood.

Painting in Arabic gave Adnan a new way of realizing the Arabic script and a new language in which to express herself politically as an Arab. Her creative output over a long career featured movement between languages, among them English, French, and Arabic. Although Adnan never became fluent in Arabic, she formed an intimate and lasting relationship with the language and its alphabet through her calligraphic painting. The items in this case demonstrate Adnan’s various uses of painting, poetry, handwriting, and repetition in her life and art.

Leporellos: Writing and Image

The accordion book form, or “leporello,” became Adnan's favorite structure for working with calligraphy alongside painted imagery. The accordion book’s ability to unfold into a vast expanse of page allows for great artistic possibility, where words can be repeated, taking on a meditative quality.

On the below leporello, made in 2012, Adnan writes the Arabic word al-bahr, meaning “the ocean” or “the sea,” rhythmically repeating across the unfolding landscape. Shown here in its "opened" state, we can see how geometric shapes and fluid lines, evocative of an ocean’s surface, share space with the calligraphy. An impression of Adnan’s presence in the creative process manifests itself in the repetition of these hand-drawn elements.

Below: Etel Adnan, al-Bahr, 2012, Japanese ink, pencil, watercolor, and colored aquarelle pencil on paper, 60 pages, 21.5 x 9 cm. each, 540 cm. extended. Reproduced in Etel Adnan in All Her Dimensions, exh. cat. (Doha: Arab Museum of Modern Art, 2014). UC Berkeley Library collection.

Alif Gallery exhibition, 1983

In 1983, when the Alif Gallery opened in Washington, D.C. with a mission to promote art from the Arab world, it dedicated its first exhibition to the work of Etel Adnan. The exhibition brochure features a short statement essay by Adnan that offers unique perspective into her conception of her leporellos. "My purpose is to consider these painted manuscripts as contemporary Arabic calligraphy: the very opposite of the extraordinarily beautiful and formalized ancient calligraphies," she writes. "I wanted the imperfection of my script, of my handwriting, to be a kind of visual reading of the text."

Source: Art & Artist Files, Smithsonian American Art and Portrait Gallery Library, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, Washington, D.C., July 19, 2023.

The cover of Etel Adnan's exhibition brochure for Alif Gallery features a detail from one of her early leporellos, made in 1970, that engages with a text by Iraqi poet Badr Shakr al-Sayyab (1961).

Above: Etel Adnan, Al-Sayyab, The Mother and the Lost Daughter, 1970. Ink and watercolour on a Japanese book. Open, 33 x 612 cm. Donation Claude & France Lemand. Museum, Institut du monde arabe, Paris. © Etel Adnan. Courtesy Galerie Claude Lemand, Paris.

Bay Area Images and Communities

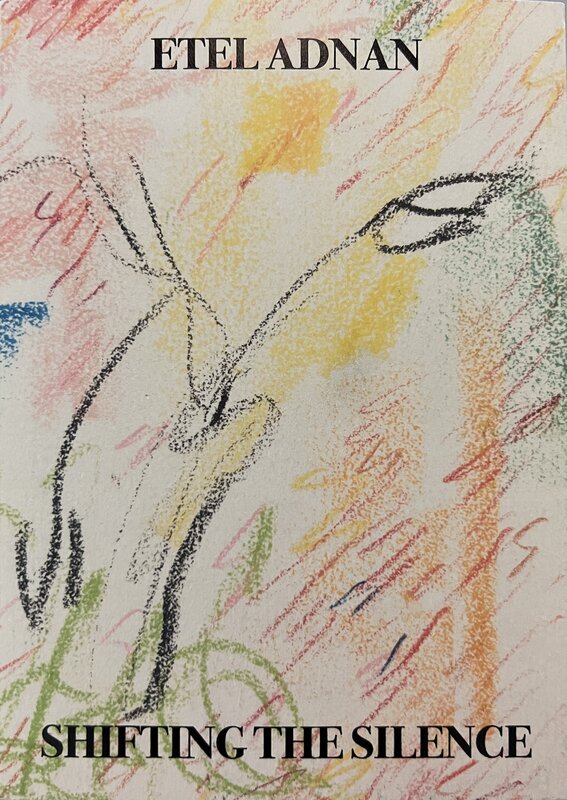

Right: Nightboat Books, "Shifting the Silence cover art." Instagram, October 28, 2020, https://tinyurl.com/bdhcfss9.

As Adnan witnessed the Vietnam War and the Algerian War of Independence from her new home in California, she began to write and publish poems in English, having fallen in love with the American culture and dialect. Spurred by the literary counterculture arising in the 1960s, Adnan found that she could fight against the war with her poetry. While living in the Bay Area and frequently traveling to countries such as Lebanon, Morocco, and Tunisia, Adnan forged deep connections with the work of modern Arabic and English-speaking poets alike, such as Mahmoud Darwish and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Adnan continued writing poetry while she began her painting career.

Until she adopted the leporello format, she practiced the two mediums separately. Adnan utilized poetry by modern Arab authors such as Darwish, copying the poems across leporellos while only understanding key words and phrases. She did not translate any of these Arabic poems into a language she could read. Adnan would then incorporate her own visual imagery amid the writing, satisfied with her imperfect understanding and interpretation of the poem. She compared the process to seeing beautiful scenery through a screen, “as if the screen did not erase images but toned them down and made them look more mysterious than they were.” Adnan went on to describe these works as “the opposite of classical calligraphy,” but they still represent her impact on Arab culture, artistically and politically. Though she did not write her own poems in Arabic, Adnan was insistent that she should be considered an Arab poet.

Living in Sausalito, Adnan and her partner Simone Fattal were situated among a community of writers and artists experimenting with form and grappling with similar political themes. Fattal founded the publishing company The Post-Apollo Press in 1982, which published many of Adnan’s books of poetry along with other works that dealt with themes of war, colonialism, and inequality. Additionally, Adnan designed book covers for other poets’ books as well as her own, including the press’s inaugural publication, Adnan’s book From A to Z. Fusing visual art and poetry, Adnan created a hybrid art form in which the artist's imprint was established in multiple ways.

Adnan continued to publish books of poetry up until her death in 2021. The Arab Apocalypse, displayed below, is one of her most prominent publications and marks another method of combining language with visual elements to create a poetic account of witnessing war in the Arab world. Characterized by its momentum, energy, and rejection of traditional poetic form, her poetry is noteworthy for its originality and political legacy.

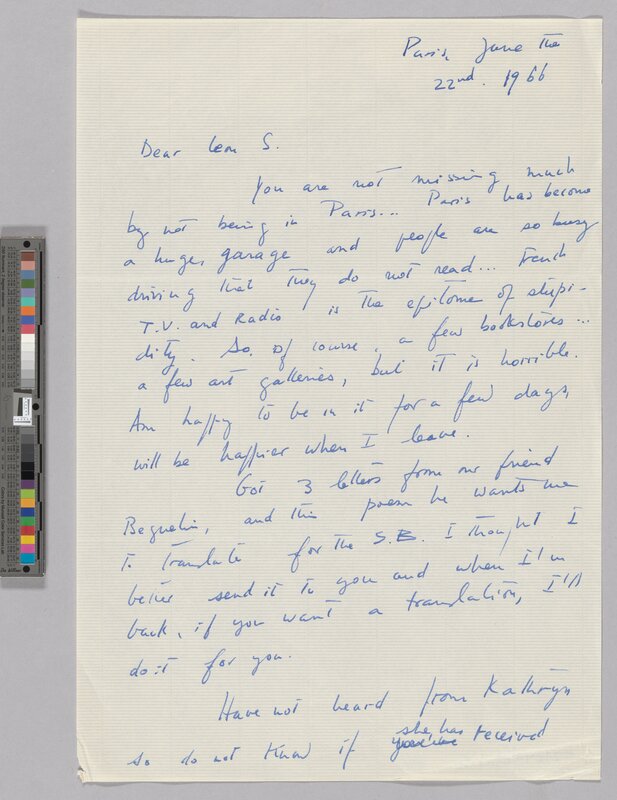

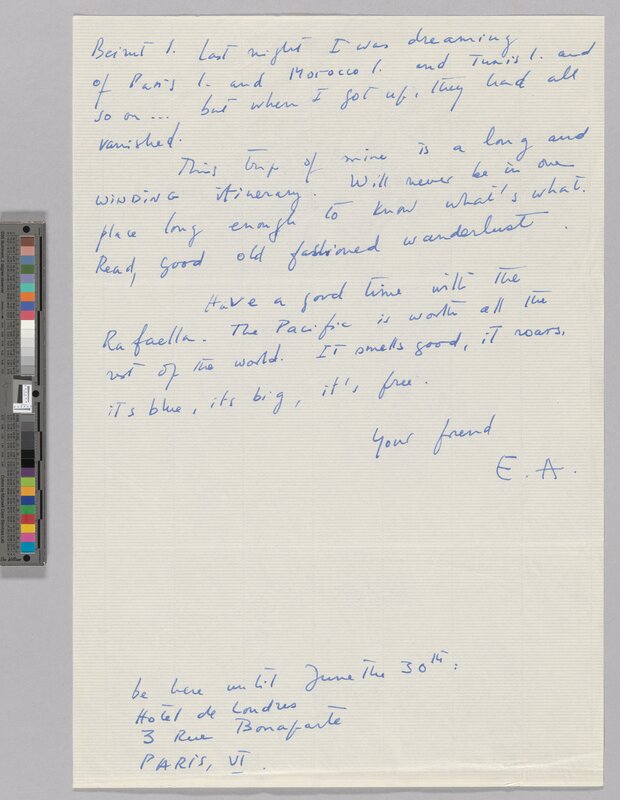

Adnan sent the below handwritten letter to Leon Spiro, the publisher of the Bay Area-based Sausalito-Belvedere Gazette, the first American publication in which Adnan had published poem. In the letter, dated 1966, Adnan writes of the chaos and clamor of Paris, her dreams, and her ever-changing experience as she moved from place to place. She concludes with a testimony to her love for the enormity of the Pacific ocean.

-

Letter from Etel Adnan to Leon Spiro, Paris, June 22, 1966 (Page 1)

Dear Leon S. You are not missing much by not being in Paris... Paris has become a huge garage and people are so busy driving that they do not read... French T.V. and radio is the epitome of stupidity. So of course, a few bookstores... a few art galleries, but it is horrible. Am happy to be in it for a few days, will be happier when I leave. Got 3 letters from our friend Beguelin, and this poem he wants me to translate for the S.B. I thought I better send it to you and when I'm back, if you want a translation, I'll do it for you. Have not heard from Kathryn so do not know if she has recieved (cont'd on next page)

-

Facsimile copy of letter from Etel Adnan to Leon Spiro, Paris, June 22, 1966 (Page 2)

Beirut I. Last night I was dreaming of Paris I. and Morocco I. and Tunis I. and so on... but when I got up, they had all vanished. This trip of mine is a long and WINDING itinerary. Will never be in one place long enough to know what's what. Real, good old fashioned wanderlust. Have a good time with the Rafaella. The Pacific is worth all the rest of the world. It smells good, it roars, it's blue, it's big, it's free. Your friend, E.A.

Above: Facsimile copy of letter from Etel Adnan to Leon Spiro, Paris, June 22, 1966. Pen on paper, 10.375 x 7.125 in. Leon Spiro papers, 1962-1972, BANC MSS 72/249 z, The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

Adnan deeply adored Mount Tamalpais, and numerous iterations of it recur across her paintings and poetry. For instance, Adnan incorporated this Bay Area peak into multiple accordion books. In the below painting, she builds a composition in angular and fluid geometric shapes of varying shades to capture the peak amid its natural landscape.

Above: Etel Adnan, Mount Tamalpais, 1985, oil on canvas, 58.3 × 49.2 in. Collection of the Sursock Museum, Beirut, Lebanon. Reproduced from Etel Adnan in All Her Dimensions, exh. cat. (Doha: Arab Museum of Modern Art, 2014). UC Berkeley Library collection.

The Post-Apollo Press: Poetry in Community

From A to Z (1982)

The cover of the first book published by The Post-Apollo Press, From A to Z (1982), is designed by Adnan’s hand. In an interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Adnan expresses, “We lose everything we have to say when we lose writing, because something written by hand says more than just words.” Such a philosophy follows the spirit of Arabic calligraphy, in which a scribe’s penmanship can change the tone and interpretation of otherwise identical passages. Handwriting allows the individuality and presence of the scribe to manifest within the content. Adnan’s bold, deliberate strokes of ink provide a personalized touch and allow insight into any underlying emotions that may be discernible within her script.

From A to Z is about Adnan’s experience witnessing the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident from afar as well as the impending threat of nuclear war throughout the 1970s. The addition of handwriting introduces a personal element to this otherwise industrial, apocalyptic setting, showing that the human touch persists in the face of environmental disaster.

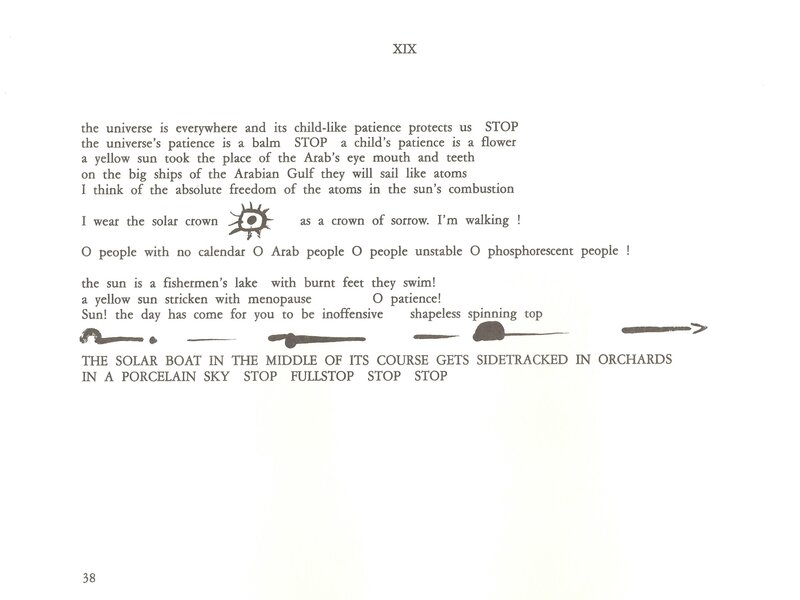

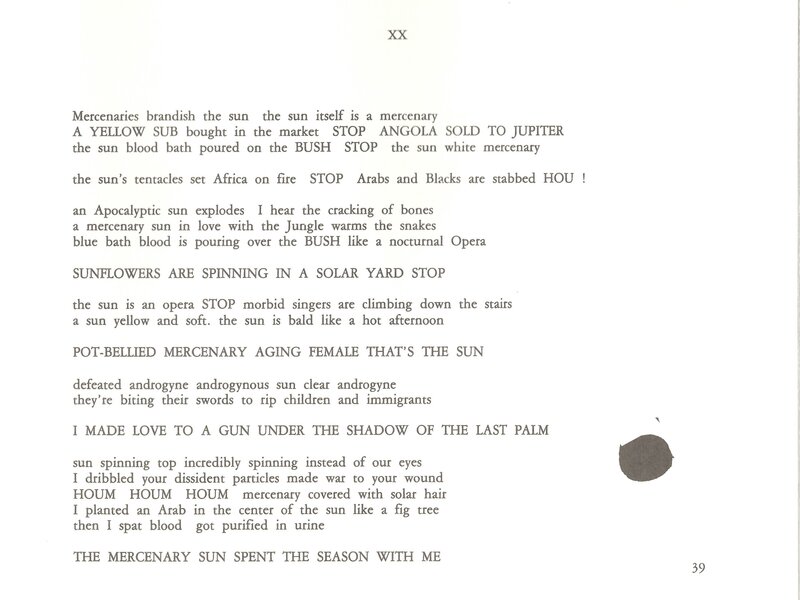

The Arab Apocalypse (English edition, 1989)

Etel Adnan originally wrote the long experimental prose poem The Arab Apocalypse in French. Drafting it in 1975 and 1976, she published it in Paris in 1980. Later, in 1989, Adnan and Fattal brought out an English edition with their Post-Apollo Press. Adnan herself did the translation.

Adnan’s poems of witness illustrate the devastating effects of colonialism and perpetual warfare on Arabic-speaking countries, including her home country of Lebanon. The sun is an active force within each poem, characterized as a ubiquitous source of energy that is effortlessly capable of inflicting indiscriminate pain and suffering. At the same time, the sun’s omnipotence is full of multitudes, more complicated than pure malevolence. Adnan’s entire body of work uses this sun motif to explore the pervasive effect of colonialism on people as well as the physical landscape they inhabit. She created countless paintings of multicolored suns, embodying them visually and literally.

Throughout the writing process, Adnan instinctively drew in glyphs whenever she felt her emotions were in such excess that words alone could not express them. Though the glyphs do not possess any definite meaning, they work in tandem with the literature as visual guides that influence the momentum and emphasis of each poem.

Below: Etel Adnan, The Arab Apocalypse (Sausalito: The Post-Apollo Press, 1989). Poems 19 and 20.

Below: Etel Adnan's annotations on Poem 4 in a manuscript version of her translated The Arab Apocalypse. Credit: Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut/Hamburg.

Prior to the publication of The Arab Apocalypse, Adnan expressed reservations about writing in French, in particular during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62). Adnan believed that the outcome of the war forecasted the future of Arab unity, and so she could no longer meaningfully express herself using the language of the colonizer. In fact, her concern about the politics of language use led to her practice of “painting in Arabic.” The cover drawing on a recent re-publication provide a visual framework for the poetry within, allowing Adnan’s symbols to establish a landscape for her imagined apocalypse without the inclusion of typed text. The endpaper to the English publication, too, features a drawing consisting only of symbols.

Below left: Etel Adnan, L’Apocalypse arabe (Paris: Galerie Lelong & Co., 2021). Private collection. Below right: Detail from Etel Adnan, The Arab Apocalypse (Sausalito: The Post-Apollo Press, 1989).

Other Publications

-

Shifting the Silence

A more contemporary example of Adnan’s blending of literature and visual art, Shifting the Silence was published one year before Adnan died at age 96. In it, she considers her impending mortality and meditates upon many of the themes present within her past work, such as mountains, space, and war.

-

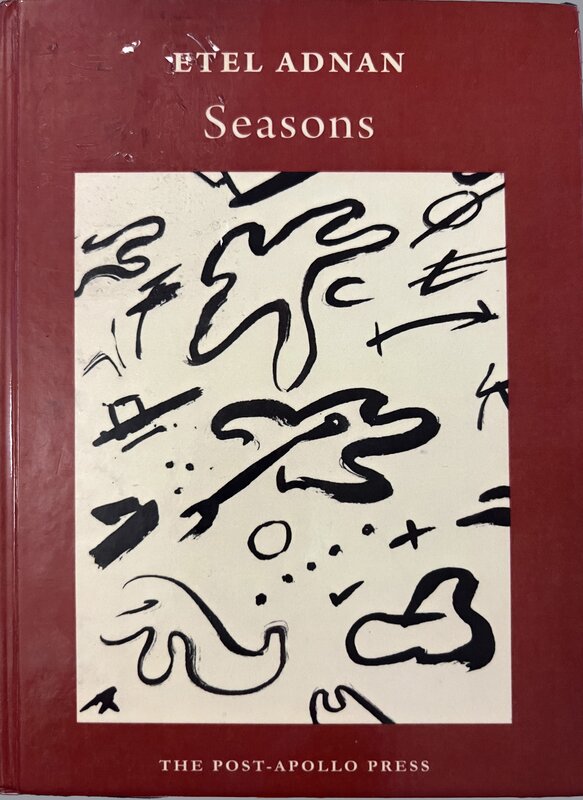

Seasons

This cover, illustrated by Adnan and designed by Simone Fattal, is a part of Contemporary Poetry Series #2 by the Post-Apollo Press. Fattal asked Adnan to make the cover art for this series along with many other books of poetry, several of which also showcase her trademark ink drawings. On this collaboration, Fattal explains, “For each book, Etel creates a new drawing, which is of course not an interpretation of the text but seems to me to be best allied with that particular collection. The choice is always due to an intangible, unexplainable intuition.”

Written by hand

Simone Fattal is an artist as well as a publisher, and has contended with many of the same themes and questions as Adnan. The below work, In Our Lands of Drought the Rain Forever is made of Bullets, text inscribed on lava stone, quotes the final lines of Adnan's poem, Jebu, about the plight of Palestinians. To this, Fattal adds the written names of locations where massacres against Palestinians have taken place, such as the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon. As such, Our Lands of Drought not only references Adnan's poetry but also her process of painting in Arabic; if handwriting is drawing, perhaps Fattal presents visual images of the massacres by evoking the names of their locations.

Below: Simone Fattal, In Our Lands of Drought the Rain Forever is made of Bullets, 2006, lines from Jebu, poem by Etel Adnan, lava stone, 300 × 200 cm © Simone Fattal. Photo: Shafeek Nalakath, Credit: Deichtorhallen Hamburg.

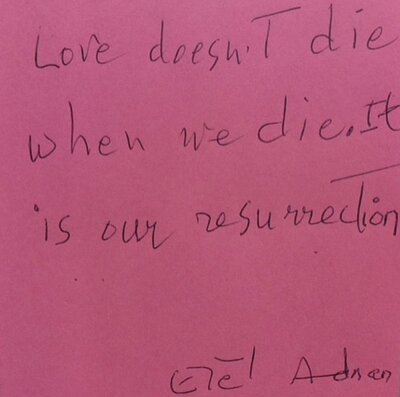

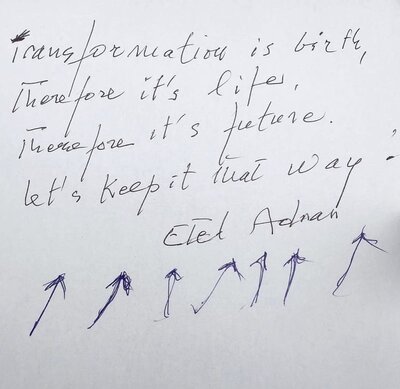

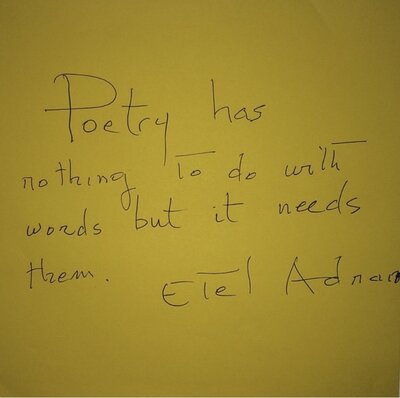

Meanwhile, traces of Adnan's own handwriting multiply beyond simply her artwork. Friends and collaborators, among them curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, collect and sometimes display notes in the artist's hand: aphorisms, insights, and expressions of love.

Above: Sticky Notes, reproduced from online documentation of Hans Ulrich Obrist Archives - Chapter 2: Etel Adnan, drawn from The HUO Archive, Chicago.

Related Content