Saleh al-Jumaie: Baghdad’s print culture in exile, 1980s

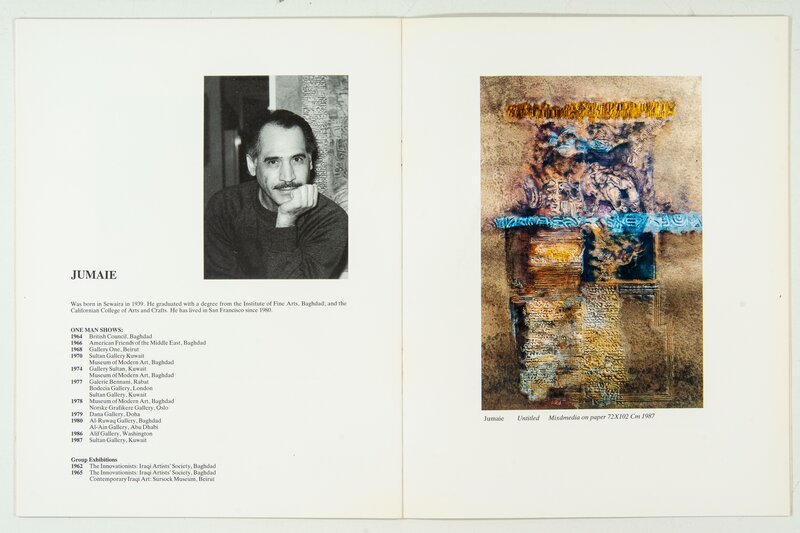

Over a long career as a fine artist, Saleh al-Jumaie (b. Suweira, Iraq, 1939) has derived inspiration from his profession in the commercial printing and design fields. He studied at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, completing a certificate there in 1962. This was followed by a fellowship supporting study abroad in the Bay Area at the California College of the Arts and Crafts (what is now CCA). Upon his return to Iraq in 1964, al-Jumaie participated in establishing a new group called "the Innovationists," and began to produce work out of found materials he gathered from the print shop: cast-off borders of metal plates, hammered into textured sheets, and more. Al-Jumaie also honed his skills in fine art printmaking techniques. In 1976, he returned to California and completed a BFA degree at the CCA in 1978 (there meeting his wife Jane Taitano, also an artist).

Although al-Jumaie returned to Baghdad upon completion of his BFA and expected to resume creative work in Iraq, the rise of Saddam Hussein to power in Iraq created a climate of political intimidation and violence that soon made it impossible to stay. In 1980, al-Jumaie fled with his family to Beirut, where he secured a teaching appointment at Beirut University College, then fled again to Northern California in 1981 as the Lebanese civil wars intensified. From the 1980s onward, he has pursued creative work in the Bay Area while working as a professional film stripper in commercial print shops.

Baghdad: A hub for experimental graphic arts in the 1970s

The three Iraqi artists featured in this exhibition, Saleh al-Jumaie, Dia al-Azzawi, and Rafa al-Nasiri, each developed an abiding interest in experimental graphic arts. A key Iraqi institution for supporting technical experimentation was the print shop and press run by designer Nadhim Ramzi in Baghdad (and later in London). Employing artists as designers, and agreeing to print many exhibition brochures and art publications, it served as a hub for innovation in page design and image production.

The display board above, which student-curators created for the exhibition in Brown Gallery, shows images from the Ramzi print facilities (upper left and lower right). The four posters, each designed by Dia al-Azzawi to advertise group exhibitions in the 1970s, were all printed at Ramzi's shop.

Exhibiting outside Iraq

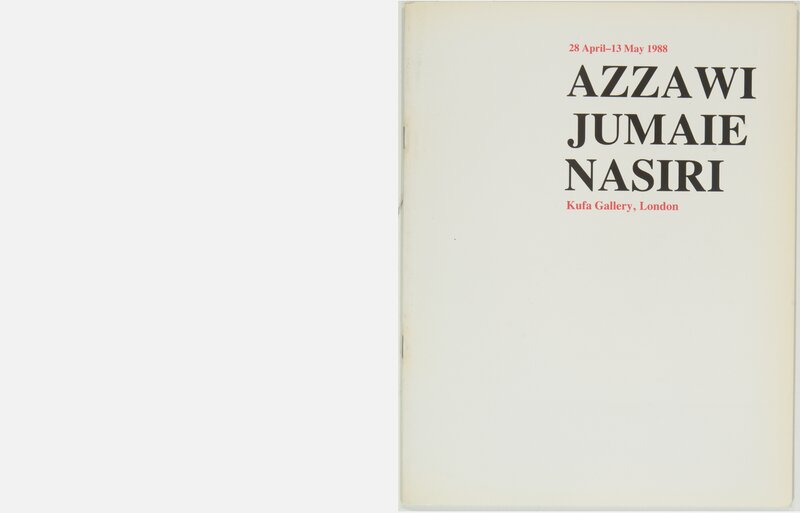

In the 1980s, a decade when many artists left Iraq, Dia al-Azzawi, Rafa al-Nasiri, and Saleh al-Jumaie continued to exhibit together, but at galleries abroad. A key institution for Iraqi artists who had once shown in Iraqi national galleries but who sought opportunities to attract international recognition was the Kufa Gallery, in London, which offered a space for visibility beyond the control of the authoritarian regime. Established by Iraqi architect Mohamed Makiya in 1985 and programmed by Rose Issa, the Kufa Gallery aimed to further the Iraqi cultural movement and Arab and Islamic arts from a position abroad, in the market center of London. The triple exhibition seen below opened on April 28, 1988, and featured lithographs, collages, and paintings by these three artists. By then, both Azzawi and al-Jumaie had left Iraq. Al-Nasiri would leave in 1990.

A Closer Look: Details from Saleh al-Jumaie's work with letters

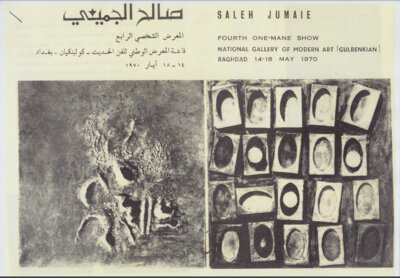

Use of printing textures, 1969-1971

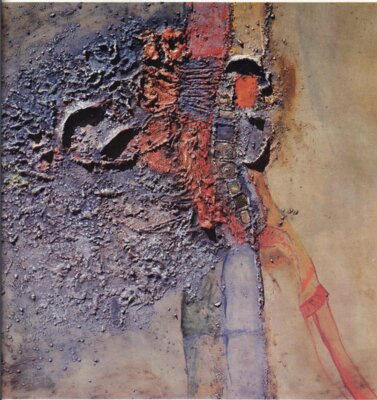

Al-Jumaie's artistic works are especially innovative in their response to print culture. While working at Ramzi's shop in Baghdad in the late 1960s and early 1970s, he experimented with using embossed textures and sign systems in a latent rather than fully expressed state as elements in his paintings. Sometimes adding layers of dust and pigment to those textures, al-Jumaie exaggerated the relief quality of the compositions. His paintings often harkened to a particular Iraqi history of developments in writing systems thought to begin with Mesopotamian cuneiform incised on clay tablets and later pass through Arabic in all its many codified forms.

Images: Untitled, 1969, from the Ibrahimi Collection; Cover images to a 1970 exhibition, Sultan Gallery archive; "Figure and Letters," 1971, reproduced in Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, The Grass Roots of Iraqi Art (St. Helier, UK: Wasit Graphic and Publishing, 1983), 61.

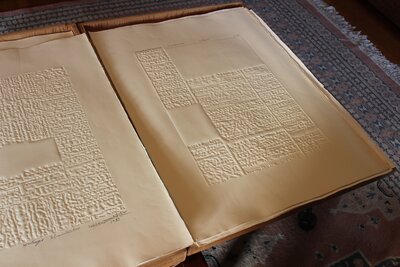

Etching and control: Saleh al-Jumaie, printing proof, c. 1980-1

Starting in the late 1970s, al-Jumaie began to make prints that responded to an intensifying atmosphere of suppressed speech. This work, a printing proof from 1980-81 that the artist loaned to our exhibition, incorporates into its overall composition small etching plates bearing messages of control. The left-most block reads “Not fit to be printed,” and is signed by “the censor.” The pencil annotations on the bottom block show al-Jumaie to be experimenting with additional stamps and seals that point to the kinds of everyday surveillance that defined his and his colleagues’ lives.

Once al-Jumaie arrived in the Bay Area, he leveraged his printing skills to secure work as a master film stripper for printing companies and as a freelance designer. Soon, he returned to the printing press as a way to create fine art. A first step involved an affiliation at Kala Art Institute in Berkeley, which offered access to high-quality printmaking facilities. After a short stint there, al-Jumaie began to develop his own facilities and experimental approaches.

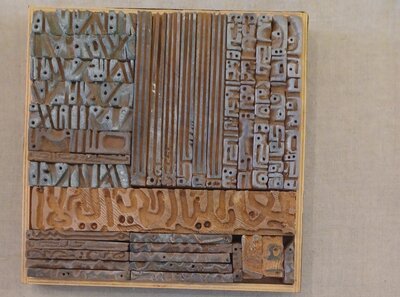

Prints and blocks from the Writings, Letters, and Journals series

While working at Kala Art Institute, al-Jumaie began to produce series of un-inked prints comprised of embossed fields of unreadable text: "Writings," "Letters," and "Journals"--the latter a direct reference to the empty political speech found in Iraqi newspaper pages. Al-Jumaie’s creative process involved carving pseudo-cuneiform language out of wood pieces, laying them out in massive arrays, and running them through a press to use pressure to produce relief prints of hollow, inaccessible testimony.

Al-Jumaie devised a labor-intensive process of carving patterns into salvaged pieces of walnut, Douglas fir, redwood, poplar, and other available woods. Most are mere simulations of script and remain completely illegible. Occasionally, however, al-Jumaie carved legible Arabic phrases—such as Basmalah ("in the name of God"), a conventional heading in texts and an opening phrase for speeches, or watani ("my homeland")—into the wood. These appear as visual and conceptual punctuation in the prints.

Although al-Jumaie's work circa 1983 was informed by his personal experience of intimidation and eventual exile after Saddam Hussein took power in Iraq, he used his aesthetic of fragmentary language to also express the dispossession of others, including Palestinians in refugee camps and Lebanese citizens during the civil war.

Arab Perspectives, Interior cover and title page, vol. 7 (April-May-June, 1986).

In this issue of Arab Perspectives, a publication of the Arab League’s Arab Information Center, al-Jumaie is the subject of a feature article coinciding with his solo exhibition at Alif Gallery in Washington D.C. By 1986, al-Jumaie was working with embossed textures and cuneiform-like words in metal and paint as well as paper-based arts. He exhibited several series titled "Pages from Old Books," using dimensional traces of text as a visual means to weave together past, present, and future compendia of knowledge.

Hear Saleh al-Jumaie speak in his own voice about his life and work, with emphasis on his personal relationship to Arabic letters:

Printing Silence: A Feature on Iraqi Artist Saleh al-Jumaie, 2023, 6 minutes and 31 seconds. Created by Teddi Haynes, Anneka Lenssen, Jasmine Nadal-Chung, and Reyansh Satishkumar, the film draws upon interviews conducted with al-Jumaie in Sacramento, California, in 2022.

Related Content