The Boat of Creed: How is it composed?

The 1969 animated film How Sailed the Boat of Creed (Amentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü) is one of the first Turkish films of this type. Conceived by artist and cartoonist Tonguç Yaşar in collaboration with art historian Sezer Tansuğ, who drafted the voice-over text, the film makes use of a folk tradition of calligraphic images as a basis for its animation. In addition to a central boat-shaped calligram drawn from popular Islamic visual culture, a range of zoomorphic figures that are formed out of Arabic letters populate the film. Termed “Boat of Creed,” or “Amentü Gemisi” in Turkish, the boat calligram is based upon a series of repeating characters - the letter vav (a word meaning 'and' in Arabic and in Ottoman Turkish) - that serve as oars. At the time of the creation of the animation, the so-called Boat of Creed had become a relatively common wall decoration in the homes and workplaces of Turkish Muslims and was associated with popular piety and expression.

In creating this animation, Yaşar not only activated traditional calligraphy practices in new ways, but he also intervened in what he and his collaborator Tansuğ considered to be a disjunctive modern Turkish culture based in part on “abandoned” symbolic language. Both creators were engaged in cultural critique and commentary. As Tansuğ has explained, he took the purpose of creating art to be a task of providing a contemporary direction to existing forms, thereby giving them a new stance. Their collaboration on How Sailed the Boat of Creed thus proposed to reactivate tradition—raising questions about how faith has served as motivation for actions—in an appeal to contemporary audiences who might themselves be seeking a changed relationship to the world. It screened at festivals in Turkey and France.

Above: Amentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü (How Sailed the Boat of Creed), directed and animated by Tonguç Yaşar, script by Sezer Tansuğ (Turkey, 1969).

Adding context to the potential cultural critique to be found in The Boat of Creed animation, it is helpful to note that Yaşar regularly published political cartoons. The very same year the animated film was released, 1969, saw the publication of a collection of his cartooning work. Relatively liberal cultural policies and increasing consumption of entertainment in Turkey in the 1960s led to the popularization of journals and cartoons in cities, which gave the author a platform to address current events.

Left: Tonguç Yaşar, Sülüname (Istanbul: E. Yayınlar, 1969), a compilation of political cartoons. UC Berkeley Library Collection.

The cartoon on Page 59 depicts a man in a cowboy hat riding a horse while clasping the first letter in the Arabic word for God (the alif) like a sword. The caricature, which may allude to the influence of the United States in Turkey, highlight Yaşar’s concerns about pressures (foreign and domestic) on Turkish society. The image suggests that the artist possessed misgivings about political applications of religion at the time.

Learning to recognize the vav | و and its uses

The letter vav/waw - as an image

Right: Statue of the letter vav/waw, 21st century collectible, metal painted gold and mounted on a wood base. Private collection. This sculpture offers an isolated image of the Arabic letter form و , pronounced as “waw” in Arabic and “vav” in Turkish, placed on a literal pedestal. The meaning of the letter vav is that of a connecting word equivalent to the English “and.” Here, its shape has been given additional aesthetic value through the decorative swirling vines carved on the side. The religious meaning of this letter derives in part from Islamic Sufi tradition and references to the divine.

Profession of belief

Above: Abdulhadi Erol Donmez, Besmele-i Şerif ve Amentü Duası (Basmala-i Sharif and Creed Prayer), 1998, ink on colored paper, 68 x 88 cm. Source: Erkan Doğanay, Vav: Mütevazı Bir Harf Hikâyesi, Vav Ve Amentü Şerhi (Istanbul: Küçükçekmece Belediyesi, 2012).

In the above work by master calligrapher Abdülhadi Erol Dönmez, the vav letter is used to visually anchor a multi-part profession of faith so as to enhance its spiritual meaning. The calligraphic composition presents elements of Islamic belief laid out in different areas, each one connected by a large rendering of the letter vav. When the vav is utilized in a horizontal series such as this one, its rhythmic visual quality amplifies the iterative conviction of the profession.

Top middle: In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful

Inside right circle: I believe in God. Inside left circle: the Exalted,

Middle: and His angels, and His Books, and His Prophets, and the Last Day, and with God's judgment of goodness and bad,

Bottom: and the Resurrection after death. I testify that there is no god but God and I testify that Muhammad is the servant, the beloved, and the Messenger of God.

Symbol of Calligraphic Prowess

Left: Ali Haydar Bayat, Hüsn-i hat bibliyografyası, 1888-1988 (Bibliography of Calligraphy, 1888-1988) (Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı, 1990).

The cover of this book depicts calligraphers at work while surrounded by an intricate vav letter. The letter vav is important to Islamic calligraphers who want to show their skill in creating a single, beautiful letter with one or few brush strokes, while also immersing themselves within the religious act of writing.

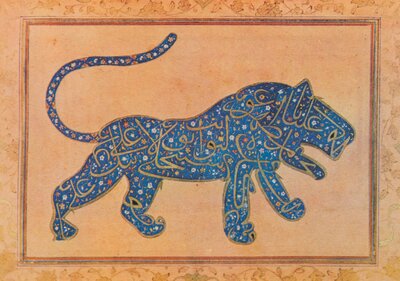

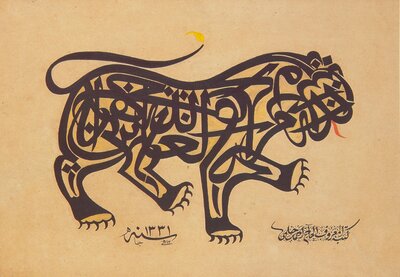

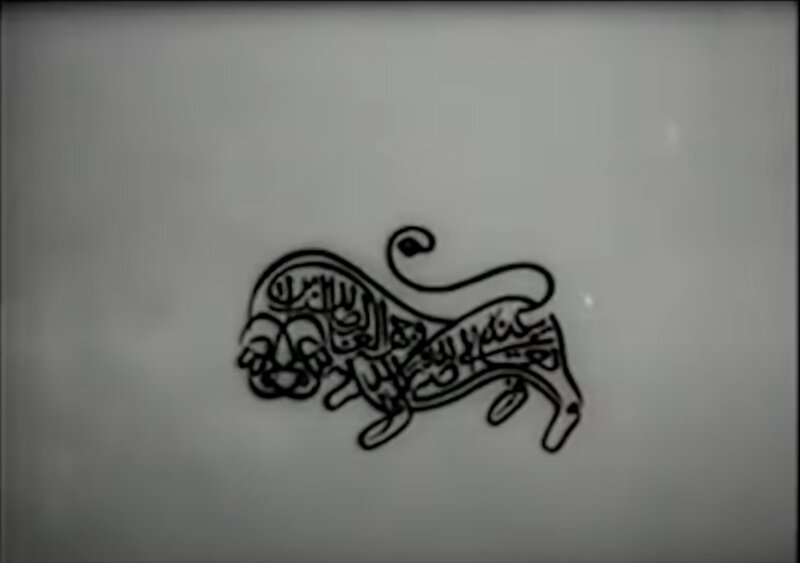

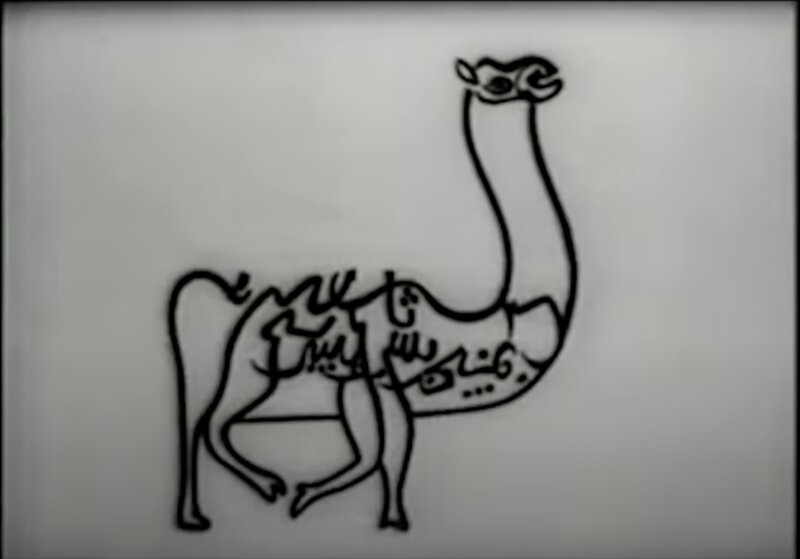

Zoomorphic calligraphy: A history

Above, left: Mir Ali Haravi, Calligraphic lion, folio in the Shah Mahmud Nishapuri album, c. 1560, color on paper. Istanbul University Library collection. Right: Ahmet Hilmi, Calligraphic lion, 1913, ink on card, Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London. Reproduced in Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art from the Khalili Collection, exh. Cat (Alexandria: Art Services, 2000). UC Berkeley Library collection.

These two lions are examples of zoomorphic calligraphy, a tendency that emerged within calligraphic practices in Ottoman Turkey. Both are written in the thuluth script. As attested by these items from different eras, calligraphers have generated this particular zoomorphic form throughout the centuries. The lion carries associations with Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth caliph and the cousin and son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad, which makes it a favored image in Shia settings as well as for Bektashi Sufis in Turkey, who venerate Ali as the “lion of God.” Other popular calligrams include everyday objects such as lamps, and animals such as camels, birds, and lions. In each case, calligraphers give the Arabic script an aesthetic visual form that nevertheless remains legible as religious writing.

Popular Turkish calligraphic arts: Boats, personified love

Above: Süleyman Berk, Ashab-ı Kehf (Companions of the Cave), 2004, ink and color on paper, 73 x 100 cm. Private collection.

Boats are common forms in Islamic calligraphic art, especially when representing religious stories or professions of faith. But the words used to create the boat form are not always the same. In this instance, a piece by Süleyman Berk, the calligraphy names elements from a story found in both Islamic and Christian traditions, albeit in different versions (sometimes dubbed the Seven Sleepers). As the story if related in the Qur'an, a number of youths fall asleep inside a cave, and through God’s power, wake up after 309 years.

Ah min’el-aşk (Oh, Love)

Right: Ah min’el-aşk (Oh, Love), 20th century, ink and color on paper, 25.5 x 35.5 cm. Collection of Bursa City Museum.

This image depicts calligraphic characters as immersed in a landscape. Mountains tremble behind Arabic characters that appear at the start of the Turkish phrase “oh, love”: a circular, heart-like letter (ha) and the vertical stroke of the alif. The heart-shaped letter—sometimes dubbed a “two-eyed letter” because of its divided center—is shown to be animated, as if it were a crying person with tears flowing into the river in front of it. Smaller text behind spells out the rest of the sentiment: “Woe upon love!” Found in popular calligraphic works in Turkey, this heart makes an appearance in the Boat of Creed animation as well.

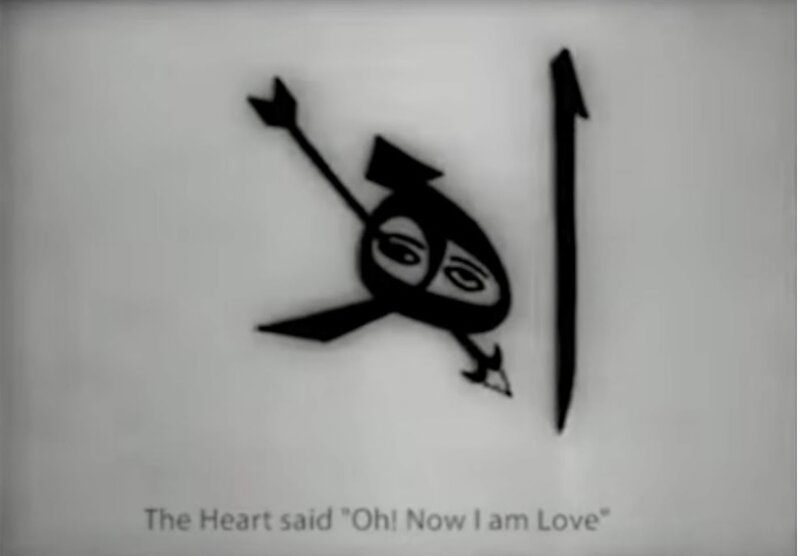

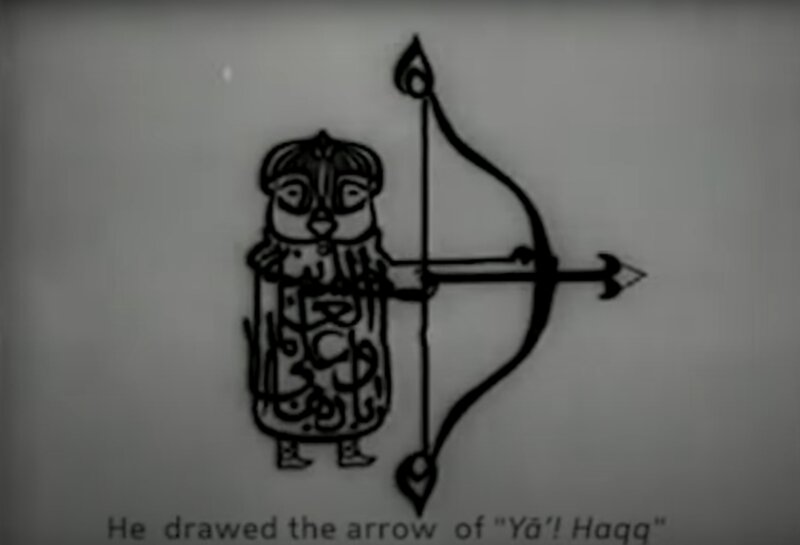

Screen captures from How Sailed the Boat of Creed (Amentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü)

-

Image of the boat, 0:10

This frame of the animation shows the composition of the Boat of Creed, in which seven vav letters are sailing a boat with a flag that has “God” written on it. In the animation, the vav’s, like humans with paddles, try to swing outside the boat to sail.

-

Image of the heart, 2:23

This is the scene where the heart is pierced by the “arrow of truth,” which allows love to be formed. The moment represents believers’ hearts being enlightened when they believe in the truth of faith, and remain true to that creed. Later, the “tears of love” will spring from the two-eyed heart to form a river and allow the Boat of Creed to sail and spread the faith.

-

Image of Hz Ali, 1:22

This frame shows the figure of Ali, known in Turkey as Hazret-i Ali or Hz Ali, formed in calligraphic letters. He is drawing the arrow of Ya Haqq, the symbol of truth. In Islamic contexts, the arrow is also interpreted as “what is right” and “reality.” Al-Haqq, the truth, is one of the names of God in the Qur’an. Shooting toward the heart, the arrow here signifies that the words of God—the truth—will create love.

-

Bird figure, 1:37

The following three images depict animals in a zoomorphic calligraphy format, an art form that tracks back to preceding centuries. Their animation here further enlivens the “living” zoomorphic texts, with the figures physically moving and acting in the space of the screen.

- Lion figure, 2:00

- Camel Figure, 2:07

Above: Selected screen captures from Amentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü (How Sailed the Boat of Creed), directed and animated by Tonguç Yaşar, script by Sezer Tansuğ (Turkey, 1969).

Related Content