Language Politics

Modernization processes in the 19th and 20th centuries, often expanding in tandem with colonial occupation, brought pressures to bear upon the Arabic script—a set of 28 characters used, with modifications, to write modern Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Kurdish, and many other languages.

During the 1920s, for example, reformers in Turkey took to declaring the complexity of the Arabic letter system as a hindrance to a contemporary society guided by scientific principles--this culminated in a 1928 alphabet law that mandated use of the Roman alphabet in place of Arabic. In South Asia in the same period, thanks to colonial policies that referenced differing linguistic communities as a basis for administrative tactics of control, the relationship of language to political identity emerged as a policy question for future independence. And in North Africa, as France exerted control over Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia as an occupying power, colonial authorities endeavored to sever educational and cultural standards from indigenous languages and cultures. This set the stage for fractious debates in the post-Independence period around policies of "Arabization" and approaches to language standardization (most often at the expense of other languages, such as Tamazight).

Turkey

What does alphabet reform look like? Cemal Nadir’s cartoon for the Turkish daily newspaper Akşam imagines an “exodus” of old Arabic from Turkish life as a long parade of alphabetic characters. The long ligatures and visual tails of Arabic are emphasized as Nadir folds them to create bodies. The use of the term “hicret” (the Turkish version of the Arabic hijra) hints at the idea of religious exodus.

Above: Cemal Nadir, Hicret! (Exodus!), cartoon published in Akşam (Dec. 1, 1928).

The Turkish state appealed to citizens in other media as well, assuring the population that simplified language would increase literacy and force a break with antiquated traditions. The below image, used as a cover to the October 12, 1928 issue of a French illustrated news weekly, is a now-famous photograph of President Mustafa Kemal standing at a blackboard to demonstrate the Latin characters that replaced the Arabic characters used to write the Turkish language.

Right: Cover of LʹIllustration (Oct. 12, 1928). UC Berkeley Library collection.

The Partition of South Asia

During the period of British control in South Asia, a colonial desire to equate language systems with peoples meant that Orientalists played a role in pressing two distinct forms of the north Indian language of Hindustani—modern Hindi and Urdu—into service to articulate polarized religious-political identities. The Partition of the region into India and Pakistan in 1947, following the end of British rule, was a violent event with massive forced migration. In its wake, Pakistan came to be defined as a Muslim nation and adopted Urdu, with its Arabic orthography, as the national language.

Below, click the titles on the right to navigate between three items:

-

Item 1, UC Berkeley Library collection

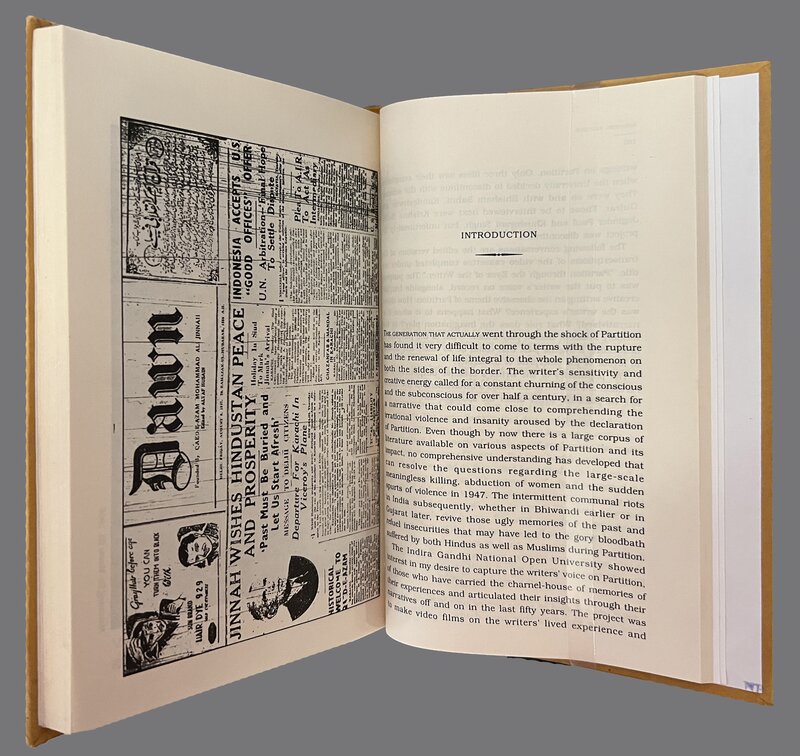

Interior pages in Sukrita Paul Kumar, Narrating Partition: Texts, Interpretations, Ideas (New Delhi: Indialog Publications, 2004), showing news clipping: “Jinnah wishes Hindustan Peace and Prosperity,” Dawn, Aug. 8, 1947. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a politician now celebrated as the founder of Pakistan, is reported to have departed from Delhi for Karachi on Aug. 7, asking his followers to leave old grudges behind and become loyal citizens of Pakistan.

-

Item 2, UC Berkeley Library collection

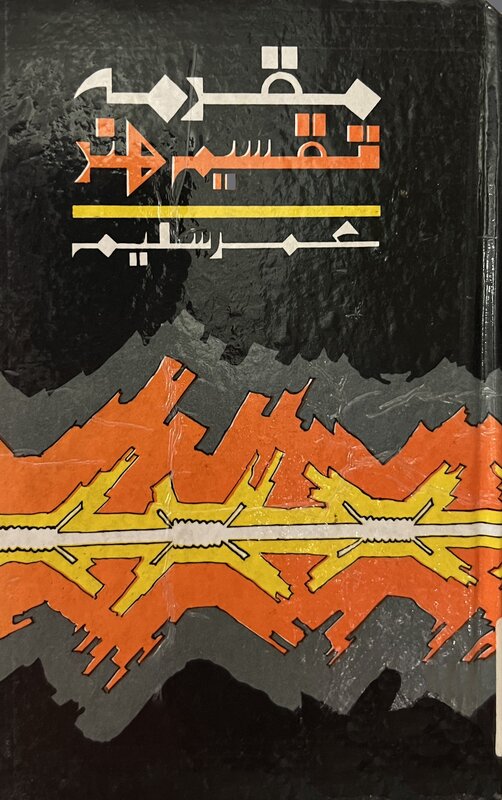

Cover of Salim Umar, Muqadamah Taqsīm-i Hind: Aik tārīḵẖ, Aik Tajziyyah (The Case of the Partition of India: History and Analysis) (Lahore: Maktabah-yi Aliyah, 1988). The book is a historical study on the 1947 Partition of India.

-

Item 3, UC Berkeley Library collection

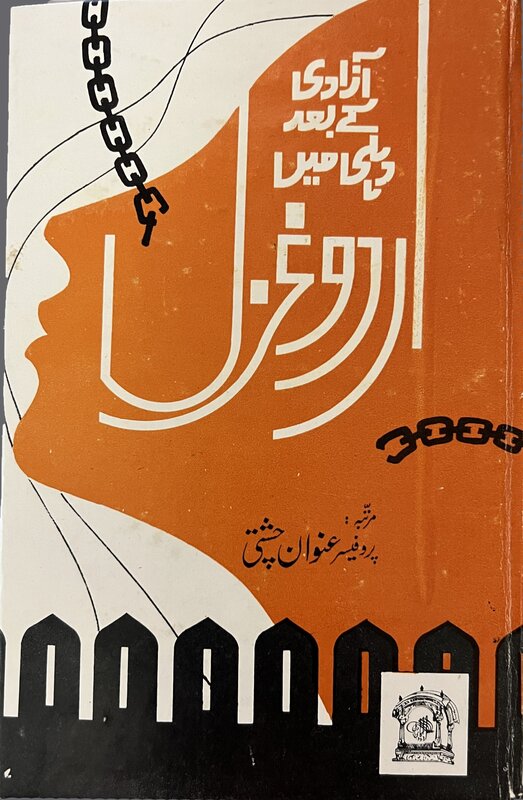

Cover of Unwan Chishti, Āzādī ke baʻd Dihlī men̲ Urdū Ghazal (Urdu Ghazal in Delhi after Independence) (New Delhi: Urdū Akādmī, 1989). This anthology gathers together Urdu ghazals composed by the Indian poet Unwan Chishti in post-Partition Delhi. Chishti was known for promoting Urdu literature in India and became head of the Department of Urdu at Jamia Millia Islamia university in New Delhi.

In the essay “Zarina’s Language Question,” scholar Aamir Mufti explores the artist Zarina [Hashmi]’s distinctive interplay of text and image in the wake of the territorial divisions that resulted from the 1947 Partition. The page shows a woodblock print by Zarina that pairs a diagrammatic composition resembling a floor plan with the Hindi-Urdu word “ghar,” meaning “house” or “home,” written in the Indo-Persian script.

Below: Zarina: Paper Like Skin, exh. Cat. (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, 2012). UC Berkeley Library collection.

Algeria

In much of North Africa, meanwhile, a near century of French occupation meant that leading writers, including anti-colonial activists, studied literature in French schools and published their texts in French. This resulted in Arabic taking on a religious connotation while French gained an association with modernity.

The clinical psychologist Karima Lazali, who practices in Algiers and Paris, has written extensively on the lasting psychosocial effects of colonial domination in Algeria and its systemic violence. Her book, Le trauma colonial, analyzes the contemporary experience of the trauma of the French colonial state’s imposition of new names on people and the land, which severed links to community, history, and genealogy. The recently published translation into English features a painting by Algerian artist Mohammed Khadda (featured elsewhere in this exhibition) on its cover.

Above, left: Karima Lazali, Le trauma colonial. Une enquête sur les effets psychiques et politiques contemporains de l’oppression coloniale en Algérie (Paris: Editions La Découverte, 2018). UC Berkeley Library collection. Right: Karima Lazali, Colonial Trauma: A Study of the Psychic and Political Consequences of Colonial Oppression in Algeria, trans. Matthew B. Smith (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2021). UC Berkeley Library collection.

To navigate to related content in the exhibition, choose from below: