Mohammed Khadda and Jean Sénac: Art for an independent Algeria

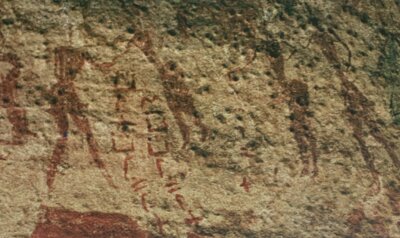

Above: Cover of Jean Sénac, poet, Mohammed Khadda, illustrations, La Rose et l’Ortie (The Rose and the Nettle) (Paris/Algiers: Rhumbs, 1964). Private collection.

Below: Interior spread from La Rose et l’Ortie (The Rose and the Nettle). A print by Khadda is paired with two lines of poetry by Sénac (roughly translated, the poetry reads: "I am the least rebellious among the living to live / I call with wounded cries the dust and the frost.")

Elements of Collaboration

Painters and poets engaged in numerous collaborations as part of Algeria’s struggle for liberation in the early 1960s and subsequent decolonization efforts, in the process probing elements of diversity and conflict within Algerian identity. Often overtly anti-colonial, these collaborations exemplify the popular resistance and revolutionary role of the art, bringing out beauty during war in a larger fight against colonial oppression. Pairing poetry with artistic illustrations, many make abstracted references to Arabic calligraphy and heritage. At the same time, they deploy French as a language of poetry and explore imagery of pre-colonial symbols and markings. As such, they grapple with the conflictual existence of various identities and languages in Algeria by referencing the multiple languages and scripts rooted in Algeria. Right: Image of Mohammed Khadda, from Révolution Africaine (Algiers, 1970) In the case of La Rose et l’Ortie (The Rose and the Nettle), published in 1964, the poet Jean Sénac collaborated with artist Mohammed Khadda. Both were committed to anti-colonial work, albeit by use of different media. Throughout, Khadda’s illustrations probe a new artistic identity for Algeria: one that draws upon Algerian traditions and history. But what does “Algerian” mean? One answer to this question was given by Abdelhamid Ben Badis, a Muslim leader who fought for Algeria’s cultural independence from France, and who famously declared “Islam is our religion, Arabic is our language, Algeria is our fatherland,” a quote which became the motto of independent Algeria. Yet Khadda's work seems to complicate the idea of a defining relationship with Arabic insofar as he references both Arabic script and Tifinagh script, the latter used by the indigenous Amazigh population. These references may indicate that Khadda’s idea of “Algeria” is not necessarily an Arabicized Algeria, but rather one that includes a mélange of cultures. As Khadda’s friend later recollected of Khadda's art, in 2016, “the signs gather in the embrace of the olive tree and the Arabic and Tifinagh calligraphy.”

Advocating for a new art meant to sustain a new, postcolonial Algeria, Khadda and his contemporaries explored ways to make good use of Algerian heritage, drawing from “our culture’s treasures that must be brought to light, from the enigmatic Tassili frescoes to the humble murals of the Ouadhias tribe.” Whereas Sénac, in 1963, stated that there was no school of art in Algeria, this changed within a year as he began identifying artists with the "School of the Noun" and the "Painters of the Sign." In this context, the fact that La Rose et l’Ortie juxtaposes abstract patterns that visually recall Arabic calligraphy with Francophone Algerian poetry emerges as an important response to Algeria’s complex language politics, which are themselves inscribed in the struggle for a post-colonial national identity. Within Khadda’s work, abstracted references to languages in Algeria reflect not only the conflictual presence of Arabic and French, but also native dialects and other scripts, such as Tifinagh. Sénac, meanwhile, identified as an Algerian poet of “graphie française,” at the same time his criticism made reference to Arabic calligraphy (despite not writing or speaking in Arabic). It has been argued that his poetry tried to contribute to native literature, linking pre-colonial and post-colonial Arabic poetry, through the use of the French language. The art on this page reflects the attempt to create an explicitly Algerian art and the emerging movement.

Language in Algeria

Following a violent seven year war, Algeria attained freedom from France in 1962. The complex question of language played a pressing role in the fight for and negotiation of Algerian national identity. French had become the most widely spoken language, and so represented a potential tool for collective expression, yet also carried a difficult and estranging legacy as an imposed colonial language.

Many Algerian politicians turned to Arabization, the implementation of Arabic as a national language and a return to a suppressed heritage. Yet there were different types of Arabic: would classical Qur’anic Arabic be favored, as a return to the nation’s culture, or would the Algerian Arabic dialect, spoken by a majority of the people, be chosen? And what of the populations using a different script and language, such as the Imazighen, who spoke Tamazight and wrote in Tifinagh?

Work by Algerian writers and artists often reflect these questions: painters Mohammed Khadda and Abdudullah Benanteur through their abstraction of sign systems, poet Jean Sénac though his identification as an Algerian poet of “graphie française," and other strategies. Through the juxtaposition of these mediums and languages, they aimed to showcase a new Algerian identity.

References in modern Algerian art

Khadda's 1964 article, "Elements for a New Art," which identifies a range of historical elements to be used in remaking Algerian art in an independent Algeria, mentions "Tassili frescoes" by name. The paintings found in Tassili n’Ajjer, in southeast Algeria, are between 3,000 and 7,000 years old. They are perhaps most renowned for their apparently naturalistic depictions of wild animals such as cows and horses as well as human figures.

Below: painting from Tassili n’Ajjer, reproduced in L'Algérie en héritage: art et histoire: exposition présentée à l'Institut du monde arabe du 7 octobre 2003 au 25 janvier 2004 (2003), UC Berkeley Library Collection

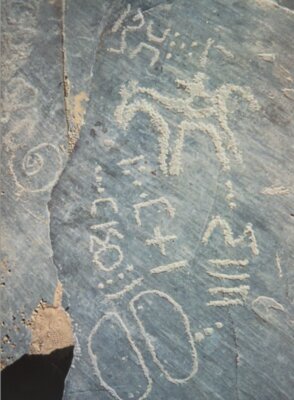

Khadda's 1964 article mentions "calligraphy" as a source for new art, too. However, he offers little further specification of the language tradition he might have in mind. Khadda's paintings in the period involved abstracting letters and linguistic signs as a basis for composition, and many scholars see in them resonances with Arabic letters (the association was encouraged by Senac, who in 1964 announced the existence of an artistic "École du Noûn," or school of the Arabic character named 'nun' and credited Khadda with recuperating the sublime aspects of Arab graphic expression). However, given Khadda's interest in the Tassili region, might it be possible he was studying the ancient inscriptions--thought by many to be precursors to Tifinagh--observable there as well?

Above: Example inscriptions, found at (left) Tiferas n'Elias, and (right) engravings at Youf Ahakit, both in Tassili n’Ajjer plateau. Reproduced in L'Algérie en héritage: art et histoire: exposition présentée à l'Institut du monde arabe du 7 octobre 2003 au 25 janvier 2004 (2003), UC Berkeley Library Collection

A closer look: La Rose et l'Ortie

The collaborative book La Rose et l'Ortie is filled with introspective yet manifestly anti-colonial poems, written by Sénac between 1959-1961. These are coupled with Khadda’s illustrations, which layer abstractions of sign systems and reference Algeria’s ancestral heritage. The juxtaposition of these art forms exemplifies what Sénac coined as “poé-peintrie,” the exploration of the fusion between painting and poetry.

Below are selected pages from Jean Sénac, poet, Mohammed Khadda, illustrations, La Rose et l’Ortie (The Rose and the Nettle) (Paris/Algiers: Rhumbs, 1964). Private collection. Click on the sound file to hear a reading of the original French as well as an English translation.

English text translations are available here (click on the title on the right to navigate):

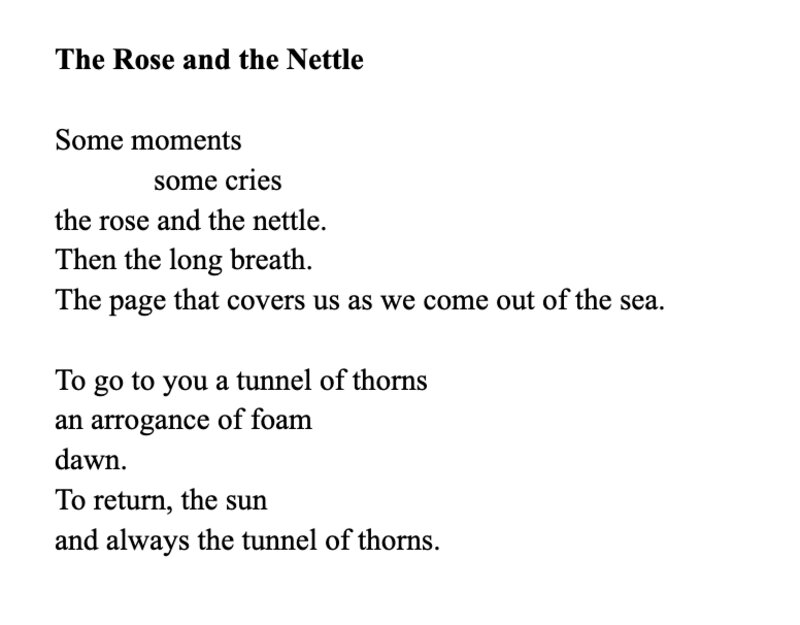

"The Rose and the Nettle"

This title poem pairs hope for a blossoming future of independence with the pain of thorns and nettle, exploring how complex relationships in revolutionary Algeria can vacillate between love and violence.

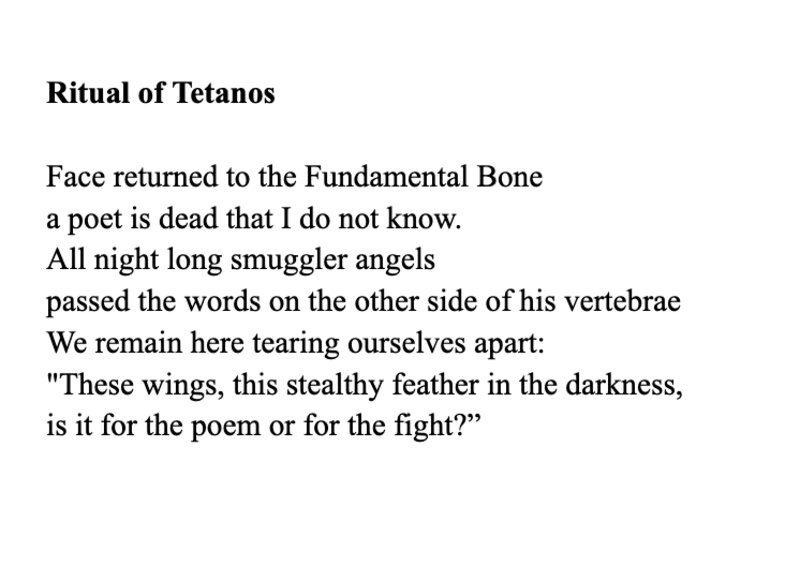

"Ritual of Tetanos"

In Rituel de Tétanos, Sénac ends with the question, "is it for the poem or the fight?" Many of his poems reflect his fervent belief in the role of poetry for revolution and his concern for a renewed relationship with the world through language. In a 1957 manifesto, Sénac wrote: “If the Algerian people are at war, it’s also because they demand the right to their poetry, their rights to poetry.”

"The Ramparts and the Sea"

Written in Sénac's mother’s native Spain, this poem, titled Les Remparts et la Mer (The Ramparts and the Sea), references the sea as a reflection of Sénac’s struggle with his own conflictual and hybrid identity. He also draws parallels between colonization in Algeria and fascism in Spain. It is paired with a painting by Khadda that evokes the colors of the caves, along with a black abstracted script imposed on top.

More collaborative art for an independent Algeria

1) A spread and a page from Jean Sénac, poet, Abdallah Benanteur, illustrations, Matinale de Mon Peuple (Dawn of my People) (Paris: Subervie, 1961). Reproduced from a copy loaned by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Library.

The 1961 book, Matinale de Mon Peuple (Dawn of my People), by Jean Sénac with illustrations by artist Abdullah Benanteur, was published before the end of the Algerian war for independence. Sénac's poems, which display an exceptional degree of revolutionary fervor, reference the rising sun as a sign of impending liberation. Accompanying ink drawings by Abdullah Benanteur, which use gestures of ink to establish horizons in the air, may also be read as evoking a rising sun or pairing obscurity with light.

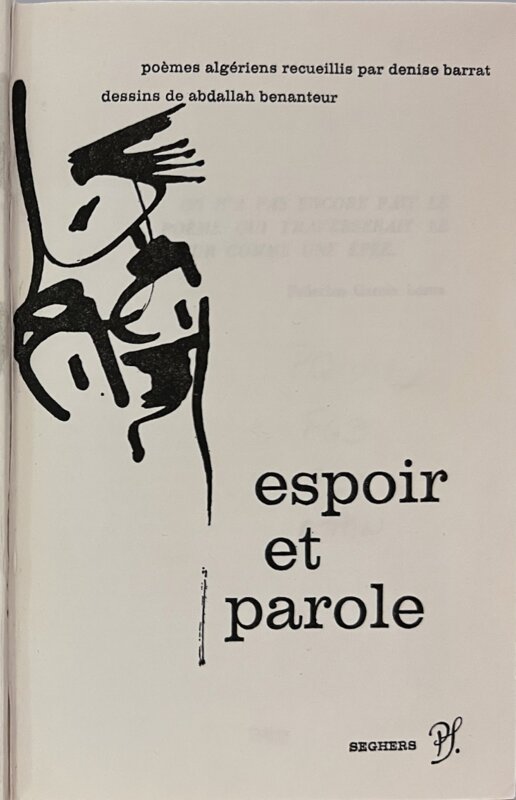

2) Title page and illustrations from Denise Barrat, editor, Espoir et parole: poèmes algériens (Hope and World: Algerian Poems) (Paris: Seghers, 1963). UC Berkeley Library collection.

In 1963, editor Denise Barrat published an anthology of Algerian resistance poetry that also features illustrations by Abdallah Benanteur. “Poetry and resistance appear like the sides of the same blade where man untiringly sharpens his dignity,” Sénac writes in the preface. The book as a whole explores the role of language and poetry through various themes central to efforts to construct an Algerian identity during the time of independence: liberty, prison, memory, torture, and war.

-

Title Page: Espoir et parole: Poèmes algériens (1963)

This compilation of Algerian revolutionary poetry was published in Paris, France, in the immediate aftermath of Independence. Artist Abdullah Benanteur's illustrations, a combination of ink drawings and lithographic prints, add a visual aspect to ongoing efforts to revive a free Algerian existence.

-

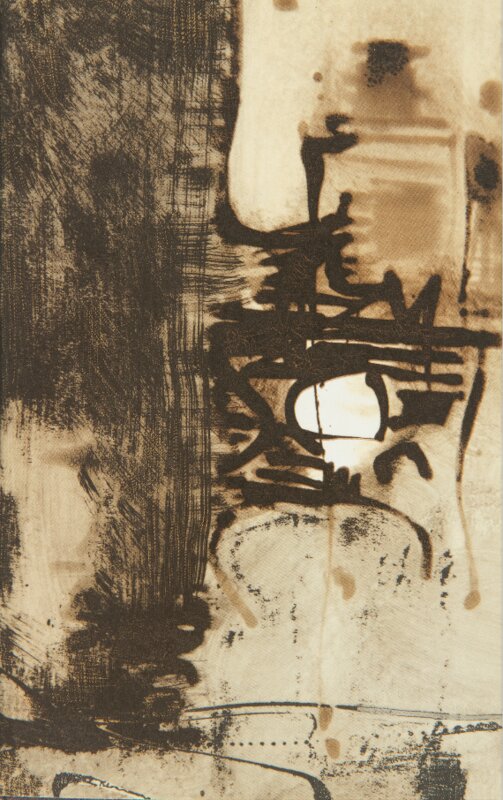

Illustration 1: Espoir et Parole

Using a palette of browns and tans, coupled with stained and burned-out surfaces, Benanteur contributes illustrations that seem to harken back in time - potentially to a precolonial world of enchanted signs.

-

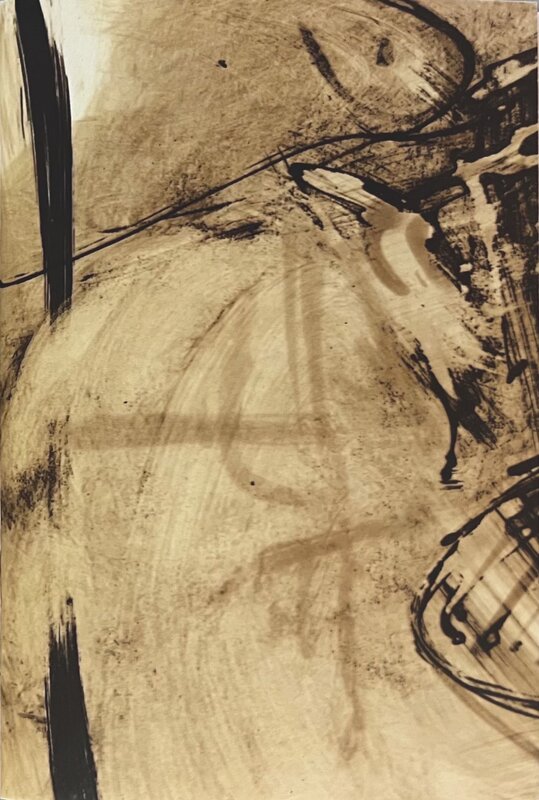

Illustration 2: Espoir et Parole Liberté

In this illustration by Benanteur, the influence of Arabic letters can be seen in the top right corner: a symbol that is similar to the Arabic letter noûn (pronounced noon). Sénac often referred to his favorite artists among the post-Independence school of art in Algeria as the "School of the Noûn."

3) Spread from Rachid Boudjedra, poet, Mohammed Khadda, illustrations, Pour ne plus rêver (To No Longer Dream) (Algiers: ANEP, 1965). UC Berkeley Library collection.

Rachid Boujedra published Pour ne plus Rêver (To No Longer Dream), a collection with poetry with art by Mohammed Khadda, in 1965. Boudjedra is important to both French and Algerian literary movements, and writes in both Arabic and French. He was a member of the Algerian resistance movement and a representative of the Front de libération nationale (FLN). He states that “writing is a form of fusing together,” echoing the interplay between cultures and languages that are prominent during this time.

4) Spreads from Bachir Hadj Ali, poet, Mohammed Khadda, illustrations, Oeuvre Poétique (Poetic Works) (Algiers: ANEP, 2005). UC Berkeley Library collection.

Khadda continued to contribute paintings and graphics to collections of poetry by colleagues. This is the case for this collection of poetry, written by Bachir Hadj Ali between 1961 and 1985, and published in 2005. Much of Hadj Ali’s writing engages with the anxieties of a post-independence Algeria. His poems feature the Arabic language, pairing it with French poetry, displaying the mix of identities present in Algeria. For example, in "Nuits Algériennes," we see an Algerian poem with French translation followed by a French poem that incorporates Arabic words- specifically repeating Khaït (خيط), meaning thread or string.

Related Content